Find Your Match, Older Writer: The Secrets of Publishing Panel

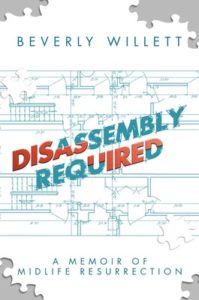

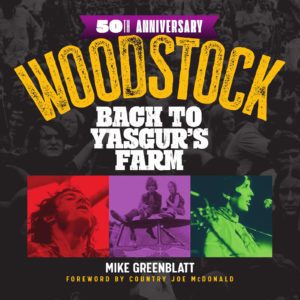

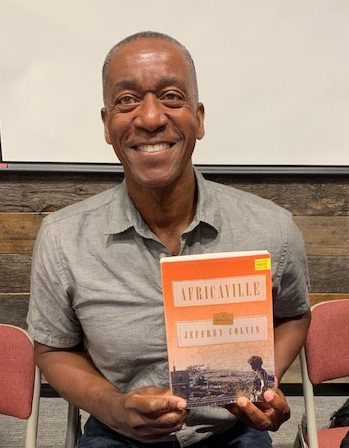

As a follow-up to my advice to a 60-year-old who wants to write, I attended another of Susan Shapiro’s inspiring “Secrets of Publishing” panels at the NYU bookstore — coincidentally, on my birthday. The panel: “Secrets of Late Bloomers,” featuring three authors who published their debut books when they were over 60 years old. The authors — memoirist Beverly Willett (Disassembly Required, the story of her traumatic divorce), Mike Greenblatt (Woodstock 50th Anniversary, and he was there at age 18, high on the brown acid), and Jeffrey Colvin (Africaville, a historical novel set in a Black community in Nova Scotia at the turn of the twentieth century) — were joined by Colvin’s agent, Ayesha Pande, Workman Publishing editor Bruce Tracy, and freelance “ghost” editor Brenda Copeland. Like the authors, Pande, Tracy, and Copeland consider themselves late bloomers, only finding their current calling well past their 40s. In fact, Tracy spoke of being an intern at the age of 31 and again at the age of 52.

All six panelists shared their journeys through other careers before becoming authors or publishing professionals. Copeland was an entertainment lawyer who recently moved from New York City to Savannah, Georgia, and the slower lifestyle gave her the opportunity to reflect on her past and expand articles she’d published in newspapers and women’s magazines into Disassembly Required. Greenblatt was a music journalist for decades, and the editor approached him to write the Woodstock retrospective because of his personal and writing experience. Colvin graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, where he majored in math, and served in the Marines before beginning a career in corporate communications. He took writing classes to become better at his day job, but discovered he enjoyed writing fiction. He began Africaville in 1999 and published short fiction in literary journals before teaming up with Pande.

All six panelists shared their journeys through other careers before becoming authors or publishing professionals. Copeland was an entertainment lawyer who recently moved from New York City to Savannah, Georgia, and the slower lifestyle gave her the opportunity to reflect on her past and expand articles she’d published in newspapers and women’s magazines into Disassembly Required. Greenblatt was a music journalist for decades, and the editor approached him to write the Woodstock retrospective because of his personal and writing experience. Colvin graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy, where he majored in math, and served in the Marines before beginning a career in corporate communications. He took writing classes to become better at his day job, but discovered he enjoyed writing fiction. He began Africaville in 1999 and published short fiction in literary journals before teaming up with Pande.

It turns out Mike Greenblatt (speaking) is Susan Shapiro’s cousin!

Pande herself had many other jobs before becoming an agent in 2005, including a stint as a condenser for Reader’s Digest and as an editor at various major publishing houses. As an editor, she found herself torn between her authors and her corporate employer, and because her sympathies usually lay with the author, she decided that agenting was a better fit. Tracy fell into publishing as a temp worker during a recession, and once there, left to try other careers (including television) and returned in his 50s. Copeland didn’t even attend university until her late 20s and was well into her 30s when she started working for Simon & Schuster. After a recent reorganization, she decided to freelance to work more directly with writers as a developmental editor and in fact served as Shapiro’s ghost editor — strong testimony to her skills.

The six panelists answered a variety of practical questions. Does one need a full manuscript, or will a proposal and sample chapters do? For fiction and memoir, a first-time author needs to submit the finished manuscript. Memoirs are particularly hard for non-celebrities to sell, and they require a lot of patience and writing skill, as well as a great story. (Try to find “the story within the story,” Tracy said.) Other nonfiction, such as the Woodstock book, sells on proposal. All of the authors began by selling short pieces first; while this is not required, it is a huge help to the older writer seeking to publish a first book traditionally. In fact, selling short pieces first is a better avenue than self-publishing early works for those seeking faster publication and notice from industry insiders.

The six panelists answered a variety of practical questions. Does one need a full manuscript, or will a proposal and sample chapters do? For fiction and memoir, a first-time author needs to submit the finished manuscript. Memoirs are particularly hard for non-celebrities to sell, and they require a lot of patience and writing skill, as well as a great story. (Try to find “the story within the story,” Tracy said.) Other nonfiction, such as the Woodstock book, sells on proposal. All of the authors began by selling short pieces first; while this is not required, it is a huge help to the older writer seeking to publish a first book traditionally. In fact, selling short pieces first is a better avenue than self-publishing early works for those seeking faster publication and notice from industry insiders.

Jeffrey Colvin holds the ARC of Africaville, due out in December, and I’m eager to read it.

Pande, who is open to both fiction and nonfiction clients, observed that writers often approach her too early. “Those familiar with publishing take their time,” she said, making sure their work has gone through multiple drafts and beta readers. She pointed out that writers only have one chance with a manuscript; once the agent has rejected that manuscript, it cannot be resumbitted unless the rejection included a R&R (revise and resubmit) request. However, the writer can requery with a new manuscript, and writers often produce more than one manuscript before one finds an agent. So don’t give up if the first one doesn’t get an agent offer or publishing home! When Pande agreed to represent Colvin, it was on the promise of his manuscript, and Africaville went through many years’ worth of revisions before she considered it ready. In fact, all three of the late bloomers wrote a lot of articles and/or drafts before their debut. They published late because it took a long time before their work was ready, and they had the patience to stick with the writing until it was ready!

Copeland discussed the value of a ghost editor for someone coming to writing later in life. Often, that person has the income and savings to hire a good editor, and having one can shorten the time to publication because the editor can eliminate wrong turns that can waste years of a writer’s life. Shapiro was one of those writers who saw the light and hired an editor; before then, she’d been trying to sell a book for seven years. (For another book that took 13 years to write and sell, she held a “book mitzvah.”)

Other good advice: Don’t burn bridges. Find a community of writers and good beta readers. Take classes. Go as far as you can on your own before looking for a ghost editor, agent, or publisher. Research agents before submitting.

The Late Bloomers panel, from left: Brenda Copeland, Bruce Tracy, Ayesha Pande, Jeffrey Colvin, Susan Shapiro, Mike Greenblatt, Beverly Willett.

In a conversation afterward with Ayesha Pande, I came to realize the importance of researching agents. Several audience members expressed concern at the tendency of young people to dominate as authors, though unlike athletics, dance, modeling, or acting, there’s no intrinsic reason why an older writer is less capable than a younger one. In fact, Pande, Tracy, and Copeland felt that older writers have had more time to develop their craft, gain life experience and reflect on that experience. However, younger agents and editors, attuned to pop culture and trends, don’t always appreciate the insights and skills of older writers. For that reason, when older writers are looking for agents, they should focus on older agents and ones who’ve represented other mature writers. It’s easy to become discouraged when younger agents reject the work of an older writer with a form letter or, even more likely, no response at all, and it may not be because the work is not good enough. It may well be the younger agent, looking for one kind of client and one kind of book, doesn’t “get” the work. So if you’re someone turning to writing later in life, or it’s taken a long time for you to develop your craft and your story, you need to find the right agent — one who appreciates age, maturity, and persistence — once you’ve taken the time and devoted the resources to make sure your work is ready to go.

Happy belated birthday, Lyn.

Sounds like a great panel. Good advice about avoiding burning bridges.

Yes. That panelist had a few scrapes over a long career but managed to patch them up before it was too late.

And thank you for the birthday wishes! I’m at the point where I’m keeping that information secret.