Not Your Superhero

Despite swearing off Twitter in favor of Instagram in 2014 after Rogue came out, I’ve been spending a lot more time on the bird app than I probably should these days. I’m learning new skills from watching others get into trouble, keeping up with the news, and lurking on kidlit-related debates.

Several weeks ago, a group of writers and agents posted about the active protagonist, and how editors’ preferences for a protagonist with a clear goal whose actions drive the story. In past years, I’ve written about the passive protagonist and how so many of my manuscripts have failed because of this. I wrote this essay after abandoning a middle grade novel with a passive protagonist. Later on I would write and revise multiple times a YA manuscript that came close at two publishers; its failure bears some responsibility for what will be a seven-year gap in my publishing career. (Perhaps my retrospective on those years should be titled “Mistakes Were Made.”)

Kids like all kinds of stories!

In the Twitter discussion, BIPOC and other creators whom society has marginalized responded that often protagonists have little control over the world around them, and under those circumstances, survival is a legitimate goal. In the eyes of editors, survival implies passivity because the protagonist is reacting to forces larger than they are rather than trying to change those forces. Editors and agents have also rejected the desire to “belong” as too passive, not a strong enough goal to drive the story. But for disabled protagonists routinely excluded from their communities, the desire to belong, to be a part of those communities we’ve watched from afar, is at the top of the list.

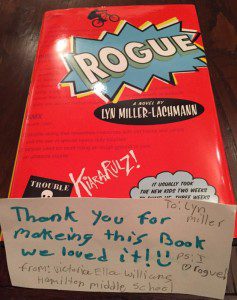

Wanting to belong, to have a friend, drives Kiara’s decision in Rogue to befriend Chad even though his family is dangerous. It drives JJ’s decision to reach out to a classmate across the racial divide because he wants to start a punk-rock band even though he has no idea how bands get together. It drives Tomáš to defy his father and his country’s secret police when he pursues a friendship with a former bully now designated an enemy of the State.

The band needs everyone!

While Kiara seeks to become a superhero like her favorite X-Men character, both JJ and Tomáš come to realize that they don’t need to be the leader or the Chosen One to achieve their goals or to grow as people. The individualistic Chosen One narrative is a Western capitalist construct in which there are leaders and followers, bosses and workers, winners and losers. But the band is much more than the frontman. Singers who get the glory would be nothing without composers, lyricists, guitarists, bassists, drummers, keyboardists, and so on. Families, natural and found, and communities can be protagonists, with the success of the group dependent on the actions of all the individuals within it.

With the pandemic, we are now coming to realize how much individualism has failed us. We need to look at other models of social organization and other kinds of narratives besides the “hero’s journey.” These include non-Western traditions, multiple points of view (including community stories like Kekla Magoon’s How It Went Down and Light It Up), and the revolutionary narratives of people challenging oppression and marginalization. We need stories of survival and belonging, the narratives of those who have lived to fight another day, and who have come together to continue the struggle. We cannot count on superheroes and Chosen Ones to save us, and our stories need to reflect this truth.

Amen. I’ve been thinking about this a lot recently, since most of my stories either involve characters reacting to a violent world or taking socially unacceptable actions (like females being violent) in response to same.

And of course these narratives are frowned on by gatekeepers. Which ensures that the dominant narratives remain the same.

Yes, this is exactly the kind of discussion that was on Twitter and what inspired me to write this post.

I had a recent discussion with an editor about his perception that the main character in my novel lacked agency and she did very little to change her circumstances … that she never even asked for a change in circumstance. I pointed out that the character’s agency was in her silence (selective mutism) and as she was in the foster care system, other than become a runaway, she had little to no control over her circumstances, except of course her silence. My opinion is that it would be unrealistic for a character in her circumstances to become actively engaged in changing them–she was in survival mode with a multitude of reasons for being so.

What the gatekeepers are missing is that by (always) giving kids agency beyond what they would normally have and having them act in a clear and decisive manner actually puts a gap between the reader and the character. Instead of encouraging them to act with the same kind of force and clarity, it may send the message to the reader that since they are not like that, they are less than … and that simply isn’t a message I will convey. Our characters need to be as flawed, diverse, and unique as the readers they engage.

I agree. Your point that kids who cannot change their circumstances read these books and feel “less than” is an important one. It actually reinforces resignation in many cases, especially if the situations and the protagonist’s actions are clearly unrealistic.

Lyn, this is so true. My civil rights books appear to be about one or a few specific heroes but they’re really about the foot soldiers. Each individual chooses whether or not to join but none can succeed without everyone else. I also fret about the impetus to make children heroic. Getting through middle school in one piece is risky enough without having to change the world. A reason we rely on children to take action is because too often adults are feckless.

Your books are a model of approaches that fiction writers can take, because they’re factual and the children you profile aren’t singled out as being special or chosen. I’m also thinking about your circus book because these were classes with ordinary kids who had no special talents.

Thank you, Lyn. I talk about being the hero in our own messy lives often. The reality is that, in our hero’s journey, we often find our community, our people, and we work together within that community. Maybe the trick is to make that community – be it family, peers, superheroes – more clearly visible.

I agree, and I think books with multiple points of view is one way of doing this, especially if the community is as much the protagonist as the people within it.

Good article; I’ve long been frustrated by the ramifications of this issue not only for the “requirements” of unrealistic protagonist agency (especially for MG) but, frequently, that of stakes — life or death, saving the world, not just emotional survival or maturation or happiness. I think it’s partly a reflection not only of Western individualism — good insight on the influence of capitalist philosophy, by the way — but male-focused, patriarchal, hierarchical norms that postulate that only the leader or outlier is important or has a story worth telling… or is the only kind that will attract male readers, or so says the conventional wisdom. Things have changed a little in the 20-ish years I’ve been doing this, but not enough, I suppose because gatekeepers are steeped in the same cultural biases as everyone else and the financial incentives are all “more of the same, with different cosmetics” not departures from what has proven to sell. Not sure how this could change without greater cultural change over a long time, though.

Thank you, Joni! Our books play a role in the cultural change, because people need to see alternatives in order to work toward them. I find Hollywood superhero movies a factor in our declining democracy because they’ve trained people to see a larger-than-life hero as the one who solves problems and vanquishes enemies. The Trump-superhero iconography and the co-optation of The Matrix by far-right groups are examples of the consequences of this kind of popular culture.