Pursuing the Hybrid Option

I’m in a lot of YA writers’ discussion groups, and one of the popular topics right now is going hybrid. Hybrid authors are ones who publish some of their books with traditional publishers while self-publishing others. There are a lot of reasons to consider this option and self-publish one or more books. Perhaps your publisher is only interested in one genre, and you would like to write in another. Your publisher has you on a schedule that has backed up your finished manuscripts for years. Your series has been cancelled before its end. You’re with a small press or e-book-only publisher that pays a tiny or no advance and has a low royalty rate, so you think you can do better financially by going it alone. You’re with a larger publisher that isn’t offering any marketing support, so you think you can do better with your own marketing push that will allow you to keep most of the book’s cover price as your own.

I’m in a lot of YA writers’ discussion groups, and one of the popular topics right now is going hybrid. Hybrid authors are ones who publish some of their books with traditional publishers while self-publishing others. There are a lot of reasons to consider this option and self-publish one or more books. Perhaps your publisher is only interested in one genre, and you would like to write in another. Your publisher has you on a schedule that has backed up your finished manuscripts for years. Your series has been cancelled before its end. You’re with a small press or e-book-only publisher that pays a tiny or no advance and has a low royalty rate, so you think you can do better financially by going it alone. You’re with a larger publisher that isn’t offering any marketing support, so you think you can do better with your own marketing push that will allow you to keep most of the book’s cover price as your own.

In her recent essay for School Library Journal, Zetta Elliott explores another important reason for self-publishing — and if you’re a reader, librarian, or teacher, buying the work of self-published authors. Zetta writes:

Publishers Weekly’s 2014 salary survey revealed that only 1 percent of industry professionals self-identify as African American (89 percent self-identify as white). That the homogeneity of the publishing workforce matches the homogeneity of published authors and their books is no coincidence. The marginalization of writers of color is the result of very deliberate decisions made by gatekeepers within the children’s literature community—editors, agents, librarians, and reviewers. These decisions place insurmountable barriers in the path of far too many talented writers of color.

I know better than to turn to the publishing industry when I seek justice for “my children:” Trayvon, Renisha, Jordan, Islan, Ramarley, Aiyana, and Tamir. I know not to hope that industry gatekeepers will rush to publish books for the children of Eric Garner as they struggle to make sense of the murder of their father at the hands of the New York Police Department. But I also know that children’s literature can help to counter the racially biased thinking that insists Michael Brown was “no angel” but rather “a demon” to be feared and destroyed. I believe there’s a direct link between the misrepresentation of Black youth as inherently criminal and the justification given by those who so brazenly take their lives.

The publishing industry can’t solve this problem single-handedly, but the erasure of Black youth from children’s literature nonetheless functions as a kind of “symbolic annihilation.”

Zetta bravely describes herself as “a writer who prioritizes social justice over popularity and/or profit.” In doing so, she has had to endure the dismissal of reviewers who consider her work vanity publishing, and critics who argue that she has chosen to eat at the segregated neighborhood place rather that fighting to integrate the publishing lunch counter. She calls her work “community publishing” because her picture books and novels are rooted in the community and appear without the mediation of large media corporations that have ignored or misrepresented African-American lives in the past. I was surprised to read that Kwame Alexander, whose verse novel The Crossover just won the Newbery Award, self-published his first 13 books for children because, as an unknown African-American writer with African-American characters, he could not break into mainstream publishing.

Zetta did break into mainstream publishing with her 2008 picture book Bird, which won the Lee & Low New Voices Award and for which illustrator Shadra Strickland won a John Steptoe Award for Illustration, given to outstanding work by an early-career author or artist. She has also traditionally published a YA time-travel, A Wish After Midnight, after initially self-publishing it, and her middle grade speculative novel Ship of Souls was also traditionally published. Since then, she has self-published as a means of controlling both the content of her work and the timetable of its release.

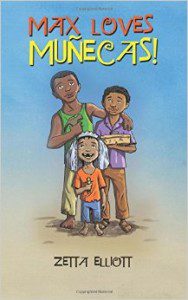

In my comment on Zetta’s article, I mentioned one of the major issues related to mainstream publishing of diverse books — the tendency of those publishers to depoliticize the books, or to publish politically tame books to begin with. One of my favorites of Zetta’s books is her self-published middle grade novel Max Loves Muñecas, a story-within-a-story set in a small city in Honduras in the 1950s and in New York City 50 years later. This age-appropriate and quite popular novel takes on two taboos — boys who like to make and play with dolls, and expropriation, injustice, and poverty in Central America. I could not see this book coming from a Big Five publisher and probably not from most smaller publishers either.

Lego minifigures illustrate a scene from the contemporary YA novel that I’m considering self-publishing.

There is an invisible corral around the children’s books that we see in bookstores and libraries, even the diverse books. Self-publishers like Zetta Elliott seek to break open that corral, creating books that grow out of the experiences of young people in diverse communities and explore topics discussed around the kitchen table or on the street but ignored or considered off-limits by big media. As I ponder what to do with one of my contemporary YA manuscripts that explores controversial topics and has not found a publishing home (or interest from editors in even reading the manuscript), I may also pursue the hybrid option.

Great post, Lyn. And it brings up an issue I wondered about–whether traditionally published authors also indie publish. I’ve thought about indie publishing the novel that was my thesis. Still thinking about that.

I was amazed to read that Kwame Alexander self-published 13 books (poetry collections, I believe) before his first traditional publication. It certainly puts to rest the adage that self-publishing will “kill your career before it starts,” as one agent warned. By self-publishing, he gained experience and got his work out there to start building an audience.

I didn’t know that about Kwame. Wow.

These are great points! I love how indie publishing allows space for books that might not otherwise be published. What a wonderful way to show different views — and, as you said, for writers to have more books out at once!

Thank you for your comment, Caryn! I’m looking forward to trying it out. I also have an out-of-print YA novel from 1987 that I’ve been slowly revising and updating and may put out there, too. I think a lot of the interest among traditionally published authors started when they wanted to bring out-of-print titles back.