Alternatives to the Individual Hero: A Place to Hang the Moon

My previous post on the problem with the individual hero in children’s and YA fiction has received a lot of attention. People have asked me for alternatives to this model. Do they exist in traditional publishing? Are they getting the readership they deserve?

In last week’s piece, I cited Kekla Magoon’s How It Went Down and its sequel, Light It Up, as examples of community stories told from many voices via their first-person narratives. In these YA novels, the community is the protagonist, and within it are individual stories of people who bring change to the community and are changed by it.

In last week’s piece, I cited Kekla Magoon’s How It Went Down and its sequel, Light It Up, as examples of community stories told from many voices via their first-person narratives. In these YA novels, the community is the protagonist, and within it are individual stories of people who bring change to the community and are changed by it.

We need to look at older narrative forms, ones from non-capitalist or pre-capitalist societies. Throughout history, the omniscient narrator has dominated literature. In this form, the author remains visible, often addressing the reader directly to offer insight and, in many types of traditional literature, moral instruction. The author reveals what each character is thinking within the same scene.

Today, this is called “head-hopping” and just about every source of writing advice warns against it. “Pick a character and present that character’s story,” they say. “Who is the character with the most important problem/most to lose/desire that drives the events within the scene or the entire novel?” I admit that I have given that advice multiple times.

Today, this is called “head-hopping” and just about every source of writing advice warns against it. “Pick a character and present that character’s story,” they say. “Who is the character with the most important problem/most to lose/desire that drives the events within the scene or the entire novel?” I admit that I have given that advice multiple times.

Omniscient narration is hard to do well, especially if readers are programmed to care only about one character. It requires caring about more than one, and even more than that, understanding that the single character is not the point of the story. It could be a family, natural or found. It could be a community, defined however the author chooses to define it.

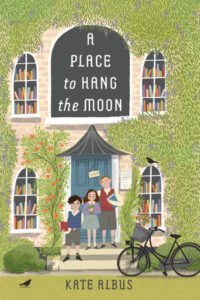

I recently finished reading Kate Albus’s debut middle grade novel A Place to Hang the Moon, which I recommend as a mentor text for anyone considering the omniscient narrative as an alternative to the individual hero. This historical novel takes place in England in 1940. The main characters are three orphans — 12-year-old William, 11-year-old Edmund, and nine-year-old Anna — who are evacuated from London to the countryside along with thousands of other children to avoid Axis bombings during World War II. Only William has any memory of his parents, and he feels responsible for his younger siblings, especially Edmund, who speaks his mind and seems to get into trouble everywhere he goes.

When the children arrive in the the village, they are hopeful — after all, this is their chance to find a real family and parents who believe they “hang the moon.” Their hopes are soon dashed when they are first billeted with selfish parents who only care about their own children — bratty twin boys William’s age who insult, steal from, and abuse the evacuees. The children then end up with an overwhelmed, impoverished mother of four children whose father is off fighting; when the government doesn’t support either the mother or the evacuees, everyone starves. William, Edmund, and Anna find refuge in the library, but the librarian is a pariah in the community because she married a German man who then left her for his country. Those in charge will not allow her to take in the children, for she is “unsuitable.”

When the children arrive in the the village, they are hopeful — after all, this is their chance to find a real family and parents who believe they “hang the moon.” Their hopes are soon dashed when they are first billeted with selfish parents who only care about their own children — bratty twin boys William’s age who insult, steal from, and abuse the evacuees. The children then end up with an overwhelmed, impoverished mother of four children whose father is off fighting; when the government doesn’t support either the mother or the evacuees, everyone starves. William, Edmund, and Anna find refuge in the library, but the librarian is a pariah in the community because she married a German man who then left her for his country. Those in charge will not allow her to take in the children, for she is “unsuitable.”

Albus maintains a strong presence as the narrator, within each scene dipping into the thoughts of her three children and the myriad of adults whose decisions affect their lives. The elegant prose and narrative choices of this historical novel made me think of a meticulously restored older home, every detail just right. The omniscient narration reflects the values and pace of a different place and time and works to create an immersive experience. The books the children read, the classic histories, adventure tales, and fantasies of the era, are the shoulders this novel stands on as Albus pays homage to the authors of the past. That alone conveys a value system anathema to our current iteration of capitalism. We do not trample or throw away what came before but appreciate it, learn from it, and build on it. We don’t throw people away either. Everyone in Albus’s novel has the possibility of redemption, even the bratty twins. No one is “better” than anyone else. No one achieves alone. But when they work together, they can solve not only their own problems but also the challenges the village faces when they don’t have enough resources on their own and are then flooded with refugees.

A Place to Hang the Moon is an outstanding example of a family story that ends up becoming a community story. I applaud its author’s persistence in bringing this unusual story to life, and the editor’s courage in going against the tide of individual superheroes. I hope it inspires more books and together they begin to change the way we look at ourselves and our communities.