Banned Books and Little Free Libraries

September 18-25 is Banned Books Week this year in the United States. In the past, people have observed this week with readings from books that had been challenged in schools and libraries over the years to raise awareness of censorship and its impact. This year feels different because of the sheer number of challenges, evidence that most of them have originated with national organizations funded by extremist dark money, and the involvement of high-ranking government officials such as Virginia’s governor Glenn Youngkin. I’ve written before about the new attacks on schools and libraries (and their expansion to bookstores) and the efforts of organizations such as PEN America and the National Coalition Against Censorship to preserve freedom of expression.

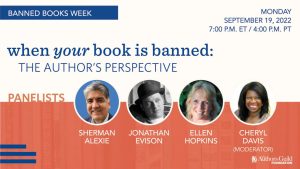

Two nights ago, I attended a panel of authors titled “When Your Book Is Banned,” sponsored by the Authors Guild. Also part of the panel was AG legal counsel Cheryl Davis. Two of the authors, Ellen Hopkins and Sherman Alexie, have written books among the 10 most often banned. They were joined by relative newcomer Jonathan Evison, whose 2018 novel Lawn Boy has been banned for its LGBTQ+ content.

Two nights ago, I attended a panel of authors titled “When Your Book Is Banned,” sponsored by the Authors Guild. Also part of the panel was AG legal counsel Cheryl Davis. Two of the authors, Ellen Hopkins and Sherman Alexie, have written books among the 10 most often banned. They were joined by relative newcomer Jonathan Evison, whose 2018 novel Lawn Boy has been banned for its LGBTQ+ content.

All three authors shared personal experiences of having their books challenged and, more recently in Evison’s case, being targeted for harassment on social media, forcing him to lock down his account. They observed that challenges had the opposite effect in most cases, leading to increased sales of their books.

All three authors shared personal experiences of having their books challenged and, more recently in Evison’s case, being targeted for harassment on social media, forcing him to lock down his account. They observed that challenges had the opposite effect in most cases, leading to increased sales of their books.

I’ve argued before (and I made the point in comments there) that the benefits of having a banned book don’t accrue equally to authors. A big name author may enjoy increased sales, but less prominent ones who depend on library sales and school visits for the bulk of their income lose out when those sales don’t happen and school visits are cancelled. One author on a panel years ago was stuck with unusable nonrefundable plane tickets when a school abruptly cancelled a visit over the content of a book. That author ended up in the hole financially. Furthermore, when a state official orders the removal of 850 books from schools and libraries (as was done in Texas), individual buyers don’t make up sales for all 850 banned authors. Maybe 20 or 30 benefit — generally the best known — while the others disappear. And with a rise in challenges and threats to arrest teachers and librarians for making banned books available, more of them will preemptively not buy potentially controversial books, and publishers will shy away from acquiring them.

As I listened to the authors discuss the problem of access — young readers who won’t be able to read books that affirm their identities and examine their society critically — it made me think of a campaign among librarians and human rights advocates some 20 years ago on behalf of independent librarians in Cuba. In 1998 a group of anti-Castro activists formed a network of private libraries to make books available to ordinary Cubans. Some of the books were banned altogether while others were only available in the National Library under very restrictive conditions: Readers had to be scholars officially recognized by the communist regime. Among the banned or suppressed books were the works of LGBTQ+ exile Reinaldo Arenas, Czech playwright and politician Václav Havel, and Mexican poet and essayist Octavio Paz.

Because other countries (notably the U.S.) sent copies of these books to the activists to fill their private libraries, the Cuban government arrested them over the next few years and charged them as foreign agents. In 2004 they were still in prison. Amnesty International condemned their detention, as did PEN and the International Federation of Library Associations.

The idea of nonprofessional librarians making books available to readers who no longer have access to them through official channels is a model for people living in repressive areas of the U.S., though anyone, teen or adult, who does so through a Little Free Library or a Banned Books Club may well face what happened to the independent librarians of Cuba, either through local law enforcement or right-wing vigilantes. But it may take a strong stand to show that a repressive community in the U.S. is no different from the kind of place its residents grew up condemning — such as the Soviet Union and its satellite states.