Do We Have a Responsibility?

My last post, “Against Monoculture,” addressed inclusion, representation, and who has the “right to write” about marginalized peoples as it pertained to literature for adult readers. However, the two recent book cancellations [added: or indefinite postponements, because at least one of these books is reportedly being revised] — Amélie Wen Zhao’s fantasy Blood Heir and Kosoko Jackson’s historical novel A Place for Wolves — were for young adult novels, and they followed several other book cancellations of YA novels and picture books in recent years.

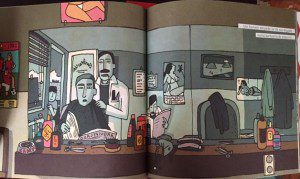

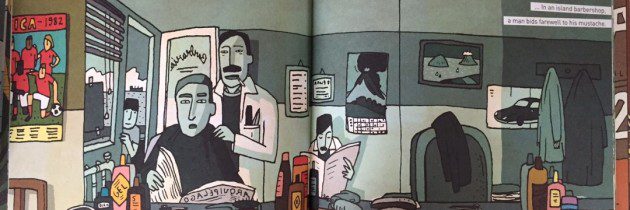

The problematic spread in the original Portuguese edition of The World in a Second.

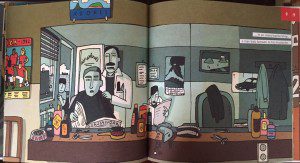

These book cancellations raise the question of whether we need to hold books for children and teens to a different standard than books for general adult readers. As an author of both middle grade and YA novels and a translator of picture books, I see how different standards are applied. For instance, picture books from Europe tend to be more frank about sex. The Portuguese edition of The World in a Second had a scene from a barbershop in the Azores that included pin-ups of scantily-clad women. While these are a staple of barbershops around the world, they would raise too many hackles in a book published in the United States, and the calendars were changed to feature cars and volcanoes as a result. A book for older readers (older MG/young YA) that I’d hoped to translate from Portuguese contained New-Age-y symbolism referring to Native Americans, stereotypes common throughout Europe. I had planned to change those metaphors to ones drawn from animals facing disappearing habitats due to human encroachment and climate change, but when the author refused I could not translate the book.

The English version, with the calendars redrawn.

One may consider these decisions an act of self-censorship, a compromise in the name of “political correctness.” However, the act of translation is in itself adapting a literary work to a new culture. Beyond making the work understandable in terms of language, it has to be accessible to an audience from a different culture, and children do not have the background and experience that adults do to make inferences and connections. Furthermore, children typically don’t purchase their own books but receive them from adults. Often, the books are taught in classrooms, and students have no choice but to read them. Ideally, controversial or problematic aspects become fodder for teachable moments, but not everyone has the same level of skill in presenting books, and classroom composition and dynamics may make a book enlightening one year and harmful the next.

My daughter teaches fifth grade, and when she brings in books that feature children on the cover who look like her predominantly African-American students, they snap up the books and read them overnight. When children see themselves in books, they realize that books are for them. When they see that the author shares their background, they realize that they too can write books and someone will publish them.

But children also need a diversity of portrayals so they know that there isn’t one thread that defines their history (slavery for African Americans, for instance, or the Holocaust for Jews), there isn’t one way people like them live, and there isn’t one genre of literature specifically “for them.” Zetta Elliott has written eloquently on the importance of science fiction for black readers, who she sees as being fed too much of a diet of urban poverty, violence, and oppression in contemporary literature.

But what about books that have aspects that adults would consider harmful or problematic? Do we apply the same standards to children’s and YA books that we do to adult titles? Most people would agree that picture books, chapter books, and middle grade titles require a greater standard of care, though the older the readers, the more capable they are of handling difficult topics such as smoking, drinking, drugs, parental dysfunction, and abuse. Many people felt that my own novel for older middle grade readers, Rogue, crossed that line in depicting a neighboring meth house and a high school drinking party to which my younger teen characters showed up. Others continued to use the book as a tool for discussion — what are unsafe situations for younger teens and what do you do when you find yourself in one? — along with other books like my friend Laurie Morrison’s powerful, thoughtful books Every Shiny Thing and Up for Air, also for older middle grade readers.

But what about books that have aspects that adults would consider harmful or problematic? Do we apply the same standards to children’s and YA books that we do to adult titles? Most people would agree that picture books, chapter books, and middle grade titles require a greater standard of care, though the older the readers, the more capable they are of handling difficult topics such as smoking, drinking, drugs, parental dysfunction, and abuse. Many people felt that my own novel for older middle grade readers, Rogue, crossed that line in depicting a neighboring meth house and a high school drinking party to which my younger teen characters showed up. Others continued to use the book as a tool for discussion — what are unsafe situations for younger teens and what do you do when you find yourself in one? — along with other books like my friend Laurie Morrison’s powerful, thoughtful books Every Shiny Thing and Up for Air, also for older middle grade readers.

Most of the recent book cancellations, though, have involved YA titles, geared to readers ages 14 and up. Furthermore, the audience for these titles include adult readers who have embraced YA literature for its fast-moving plots and emotional resonance. And here, the idea of pulling books for the purpose of protecting readers is far murkier.

On the one hand, teens who read these books rarely do in school settings because of the excessive focus on testing at that level. And when they do, they often read adult classics that may open up substantive discussions were it not for the fact that many of those classics don’t resonate with young people today the way the best of YA literature does. If we approached YA literature as literature, rather than consumer-driven entertainment with its emphasis on showing readers what they want to see about themselves, perhaps we would get a more nuanced discussion. This isn’t the fault of YA authors who are writing books of serious literary merit, but of critics who refuse to take those books seriously and thus only focus on Twitter spats rather than on the work itself.

Teen librarians and committed educators have done a lot of good work in creating reading groups and using books to build critical thinking skills and community. Rather than spending our energy debating whether or not problematic books for teens should be pulled before publication, we should make sure these people, who truly care about teens and their books, receive the support they deserve. They should be the ones leading our discussions in libraries, bookstores, schools, and community centers, in front of the logos of PEN and other organizations that can help spread the word. And this way, books with issues, good and not-so-good, will receive the same thoughtful discussion that advances knowledge and understanding, rather than those otherwise-meritorious books being automatically cancelled and the discussion shut down.

Hi, Lyn. As always, I enjoyed your thought-provoking piece. In my mind, translating (which I prefer to call “interpreting”) is at least as important as the original writing. Regarding the book that you had hoped to translate that had contained stereotypes of Native peoples: Your offering to change the racist metaphors to ones drawn from animals facing extinction–a change that the author refused and caused you to pull out of the project–was more than just a decision about one book. It was a strong stand against racism. It was seeing the whole picture. It was something we–as educators and activists–all need to do. And, as you write, we need to “build critical thinking skills and community.”

Thank you! I’m sorry the book didn’t work out, but sometimes we have to make these tough decisions.

I’m sorry to hear that the translation project fell through, Lyn. But I admire the fact that you tried to come up with a workable solution.

Great post as usual. Glad you mentioned Laurie’s book.

Thank you! Yes, I did try, but in this case, she had veto power.