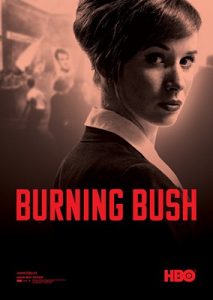

Films for the Resistance: Burning Bush

Now that I no longer have cable TV, I’m watching movies on Netflix and YouTube, among them films from other countries with English subtitles. And I’m learning a lot — not only new languages but also how people in other countries endured and resisted repression. Most recently, I saw the four-hour long, three-part series Burning Bush, which originally aired on HBO Europe in the Czech Republic and Germany. Directed by the acclaimed Polish filmmaker Agnieszka Holland, the film begins with the self-immolation of 20-year-old student Jan Palach in Prague in January 1969. Palach set himself on fire to protest the Soviet Union’s crushing of the Prague Spring five months earlier. His act of martyrdom reflected the helplessness and desperation that young people felt when their democratic uprising gave way to totalitarian oppression, seeming without end. The Czech people, in fact, would not see their beloved democracy for another 21 years, until the Velvet Revolution of 1989.

We in the United States may have a hard time understanding why Palach’s act carried the significance that it did. Although the hard-line Communist government — completely beholden to the Soviet Union and its tanks — did its best to discredit Palach and suppress information about his martyrdom, people did not forget. The violent suppression of demonstrations to mark the 20th anniversary was one of the key events that led to the Velvet Revolution ten months later. (Self-immolation serves a powerful symbol, as Mohamed Bouazizi’s fiery suicide in Tunisia to protest police violence and corruption incited the Arab Spring in 2011.) The “burning bush” — a fire that is never extinguished and never fully consumes its host — symbolizes the enduring power Palach had on the people of his country, both those who sought to crush freedom and those who fought to regain it.

We in the United States may have a hard time understanding why Palach’s act carried the significance that it did. Although the hard-line Communist government — completely beholden to the Soviet Union and its tanks — did its best to discredit Palach and suppress information about his martyrdom, people did not forget. The violent suppression of demonstrations to mark the 20th anniversary was one of the key events that led to the Velvet Revolution ten months later. (Self-immolation serves a powerful symbol, as Mohamed Bouazizi’s fiery suicide in Tunisia to protest police violence and corruption incited the Arab Spring in 2011.) The “burning bush” — a fire that is never extinguished and never fully consumes its host — symbolizes the enduring power Palach had on the people of his country, both those who sought to crush freedom and those who fought to regain it.

Burning Bush explores the impact of Palach’s suicide on various characters, real and fictional — his grieving mother and brother; the students who had formed a clandestine movement for democracy, with which Palach was tangentially affiliated (most of them composite characters); a police investigator (a fictional character) torn between the dictates of his Soviet-influenced superiors and his genuine admiration for the intrepid students; a university administrator juggling his conscience and his desire to protect his rebellious daughter; and the very real and heroic lawyer Dagmar Burešová, who represented Palach’s family and a student leader defamed by the small-town Communist Party leader Vilém Novy, a former KGB prisoner now serving his Soviet masters.

Burning Bush offers a fascinating combination of fact and invention, of particular interest to fans (and writers) of historical fiction. But what about the rest of us? Why should one devote four hours to a film set in 1960s Eastern Europe?

People who’ve lived in the United States all their lives have little or no experience of living under a totalitarian regime. If we are to take the words of our current leader at face value, all of that may change. The change may be gradual, or it may be sudden. But it’s important to see how people survived in the past and the consequences of the choices they made. So what lessons can we find in Burning Bush?

The first is what desperate people will do when deprived of both hope and freedom. Jan Palach and 18-year-old Jan Zajíc the following month, had their whole lives ahead of them, but they considered their futures to be so bleak and constrained that the best they could do was become a burning symbol of the desire for freedom. And they did become powerful symbols. Their deaths led to widespread social turmoil, long-term mobilization for democracy, and a regime’s scrambling to contain the damage.

The second is that totalitarian states are “leaky” and some institutions (particularly the judiciary) may remain in place despite their outcomes being rigged. By filing suit against Communist Party officials on behalf of the Palach family and the student leaders, Dagmar Burešová exposed the government’s corruption and lies, even though she and her clients lost the case and were fined. The government was forced to claim “national security” as the reason rather than the rightness of its position. As a lawyer, Burešová continued to be a thorn in the side of the regime as she defended the dissenters of the Charter 77 movement who eventually became the leaders of the Velvet Revolution.

The third is that most people will betray their principles and their friends to protect themselves and their families. Some will even betray their families. Trust is a scarce commodity in totalitarian societies, and love has its limits. For most people self-preservation trumps all, and the wounds of betrayal take generations to heal, if they do so at all. Which brings us to…

The fourth is that history remembers and judges. Dagmar Burešová is a human rights hero today, still alive at 88 years of age, the first Minister of Justice in the democratically-elected country after the Velvet Revolution. Her courtroom nemesis, Vilém Novy, was ultimately disgraced, so much so that his daughter, a prominent Czech TV personality, would have nothing to do with him and in fact corroborated the film’s portrayal of him as a liar, Russian collaborator, and drunk.

Update: The hero of Burning Bush, Dagmar Burešová, died on June 30, 2018, a few months before her 90th birthday. Rest In Power.

Incredible, as always, Lyn. Thank you so much!

And you should be able to see it easier than we can because HBO Europe produced it.

Thanks for the recommendation, Lyn. I no longer have cable either. I watch films on Netflix. I’m glad this is available there.

We ended up renting the film on YouTube rather than Netflix. In fact, there are a growing number of options for us who decide to cut the cord.

If only more Americans were aware how easy it is to lose your democracy to fascism, and how hard it is to get it back.

Yes. This is what my own books are about, and also how easily fascist governments destroy lives because they and their allies (employers, landowners, even neighbors with an ax to grind) have the unlimited power to do so.