Gdańsk: A Regional Tourist Destination Levels Up

My visit to the Świat w Budowie Lego gallery in Krákow was part of a four-day visit to a well-known and loved travel destination in Poland. My writing partner and her husband praised the city after their own family heritage trip (his), and I was not disappointed. Krákow is in the part of Poland that was once occupied by Austria-Hungary, and the architecture around the city’s main market evokes that of Vienna. (Many have called the city a “little Vienna.”)

Warsaw, Poland’s capital, was once part of the Russian Empire, also evident in its massive monumental architecture. Russian invaders and occupiers like buildings that are imposing, that go on and on, that make the individual feel like a bug about to be crushed.

Gdańsk is in the part of Poland that once belonged to East Prussia, and the building styles are more Germanic or even Dutch, characteristic of the cities on the coast of the North Sea and the Baltic Sea that were once part of the prosperous Hanseatic League. A crane along the Motława River dates from the fifteenth century.

It’s not the original crane, however, since the original burned several times over the centuries and was destroyed in an Allied bombing at the end of WWII. Between the two world wars, when Poland achieved its independence for the first time since the eighteenth century, Gdansk was the Free City of Danzig, divided between a German majority and a Polish minority. The nearby town of Westerplatte was the site of WWII’s first battle, as the Nazi regime moved to take over the city. At the end of the war, German ships evacuating their citizens in the area sailed from Gdańsk and nearby Gdyńia, making these cities among the last battles of the war in Poland.

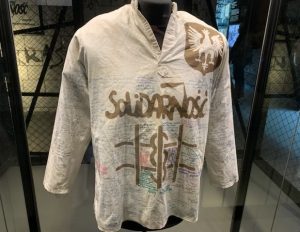

Gdańsk reentered the pages of history in August 1980, with the strike at the Lenin Shipyard that touched off the Solidarity protests throughout the country. After several weeks, the Communist government signed an agreement making Solidarity the first independent union under the Soviet-controlled regime. While the regime declared martial law a little more than a year later, on December 13, 1981, and imprisoned most of Solidarity’s leaders, resistance continued, much of it through the Catholic Church and inspired by the Polish Pope John Paul II. The regime collapsed in summer 1989, one of the first Soviet satellite nations to do so. Solidarity co-founder and shipyard electrician Lech Wałesa became Poland’s first democratically-elected leader.

Visitors to Gdańsk can witness these stories at the new (opened in 2017) Museum of the Second World War and the European Solidarity Center. Both are excellent museums. The WWII museum is quite comprehensive, touching on all of WWII history, not just that in the city and in Poland. I was especially impressed with installations of streets before (at the beginning of the exhibit) and after (at the end) all the wartime bombing. Those installations give a sense of what it’s like to live in a war-ravaged city, what many people in neighboring Ukraine are experiencing today. Much of the emphasis in this museum, as well as in various museums and sites in Warsaw and Krákow, is on the Polish underground resistance to Nazi occupation, consistent with the official line reinforced by memory laws that Poland and its people were not responsible for the Holocaust. These memory laws have been controversial — why would you suppress information if it wasn’t a source of shame and guilt for you? — but this and other WWII museums also address the collaboration of many Poles motivated by fear, profit, and/or outright antisemitism.

The European Solidarity Center exhibit begins with a model of the crane Solidarity co-founder Anna Walentynowicz operated, as her firing — three months before she was eligible for retirement — touched off the strike. There isn’t much about the organizing that took place in the decades before the strike, organizing chronicled in Andrzej Wajda’s films Man of Marble and Man of Iron, but visitors see the events during the monthlong strike, in the period between September 1980 and December 1981 when 10 million Polish people joined Solidarity, and in the following eight years when the activists endured arrest, interrogation, prison, and in some cases death while building the internal and international support that ultimately toppled the Communist regime.

Among those who paid the ultimate price were several Catholic priests (the most prominent of them Jerzy Popiełuszko, assassinated in 1984 at the age of 37) and aspiring teenage writer Grzegorz Przemyk, the son of a prominent poet and the subject of the recent film Leave No Traces. Most of the Solidarity prisoners were incarcerated together, under far more harsh conditions than ordinary prisoners, but that segregation also allowed them to strengthen their connections to each other, connections that would help them to negotiate the transition to democratic government.

- WWII lighthouse Westerplatte

- kayakers on the river

- loading the coal

- double-decker carousel

- The old crane

- newer crane

Outside the museums, visitors can walk the charming streets and enjoy local cuisine, which is less meat-heavy than elsewhere in the country and more focused on fish, including the smoked fish popular throughout the Baltic region. For the young and young-at-heart, there’s a beautiful double-decker carousel and a Ferris wheel that offers a panoramic view of the city. I took a boat trip along the river to Westerplatte, where one can note the impressive size of the shipyard where the Solidarity movement began. As the river approaches Gdańsk Bay and the Baltic Sea, the shipyard gives way to a port facility, where coal and grain waited to be loaded onto ships. Further on, a bombed-out watchtower marks the first WWII battle. And at the end of the ride, one can look across the bay at the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad, always a threat as the Bad Bear seeks the restoration of its empire.

Gdańsk is above the 54th parallel, about the same latitude as the southern islands of Alaska. In the winter there’s not a lot of sunlight, but days are long in the summer. It’s reachable from the south by frequent and fast train service from Warsaw and from the north and west by ferries with hotel-like (but smaller) rooms and ample dining and entertainment options leaving from several ports in Sweden. It’s no surprise to see a lot of tourists from Sweden, and other driving over from Germany. However, the this charming city of a little under half a million people deserves to be more than just a regional destination.

Beautiful photos, Lyn! How wonderful that you were able to visit and enjoy such historic places.