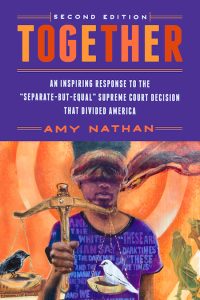

Joining Together for Civil Rights: An Interview With Author Amy Nathan

As I pointed out in my last blog post, I’m highlighting outstanding and important books by author colleagues. With the flurry of end-of-session rulings by the Supreme Court, Amy Nathan’s Together casts light on a late nineteenth century ruling, Plessy v. Ferguson, which legalized racial segregation in the United States until the Brown decision overturned it in 1954. Still, there was much work to be done.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Amy about the recently-published second edition of her book and advice she had for others writing nonfiction based in part on oral history.

I had the pleasure of interviewing Amy about the recently-published second edition of her book and advice she had for others writing nonfiction based in part on oral history.

What inspired you to write the original version of Together, and what inspired you to update it?

What sparked my interest was a surprising Washington Post article I saw in June of 2011, the same year my book Round and Round Together was published. That book describes how Black and white citizens from varied religious, educational, and philosophical backgrounds came together in 1963 to end segregation at an amusement park in Baltimore, my hometown. I was primed to be interested in other examples of people working together and the Washington Post story did exactly that, introducing me to a powerfully symbolic example: a new foundation in New Orleans created by two descendants of the opposite sides in one of the U.S. Supreme Court’s most pernicious decisions, Plessy v. Ferguson.

I was very familiar with that 1896 court decision, having explained in Round and Round Together how it had provoked the need for civil rights protests from the early 1900s on, including in Baltimore. That decision had established “separate-but-equal” as the legal underpinning for decades of Jim Crow segregation. In Round and Round Together, I also showed how the overturning of that principle had a major impact on the slice of Baltimore history the book highlights. When a new set of Supreme Court justices in 1954 officially overturned “separate-but-equal” with the Brown v. Board of Education decision, Baltimore activists started protests the very next summer at the city’s amusement park. If schools could desegregate, why not amusement parks?

So, I had been doing a lot of thinking about Plessy v. Ferguson. But I never knew about the Plessy & Ferguson Foundation until I read that Washington Post article. The two descendants who created the foundation are Keith Plessy and Phoebe Ferguson. That they would decide to work together seemed amazing—and wonderful—to me. Keith’s ancestor was Homer Plessy, whose arrest in 1892 for sitting in a train car for white riders was part of an organized effort to challenge the constitutionality of Louisiana’s train segregation law. Phoebe’s great-great-grandfather was the local judge who ruled against Homer Plessy, leading to the case landing at the U.S. Supreme Court. Keith and Phoebe were both born in New Orleans in 1957 but didn’t meet until they were in their 40s. By then, they were ready to change the ending of the story that links their families by creating a foundation to help people learn about the negative impact that the court case still has today, with a hope that this will encourage people to work together to create a more just future.

I decided that I had to find a way to write a book about them and their foundation.

When I proposed this idea to them, they were totally onboard with it. They were glad to be interviewed and suggested others to interview, as well as books and resources to explore. The book for adults and teens that we collaborated on—Together—intertwines a compact account of the court case with Keith and Phoebe’s personal journeys and the work of their foundation. Keith calls their foundation a “flip on the script.”

Another “flip on the script” happened several months after Together’s 2021 publication. A new District Attorney, Jason Williams, took office that year, the first New Orleans D.A. to create a Civil Rights Division to look into possible wrongful convictions. A civil rights lawyer suggested to Phoebe and Keith that maybe his office could help them win a “posthumous pardon” for Homer Plessy. They worked with the D.A. and his staff to see if that was possible. On November 11, 2021, the Louisiana Board of Pardons unanimously approved their petition for a pardon. Governor John Bel Edwards signed the pardon on January 5, 2022, almost exactly 125 years after Homer Plessy had entered a guilty plea for violating a law that today’s governor and District Attorney now thought should never have been written. At the pardon-signing ceremony, District Attorney Williams said: “While Homer Plessy’s actions at that time made him guilty of a crime under the law, it was really the law that was the crime . . . Homer Plessy was no criminal. He was then, and is now, a hero.”

Together needed an update! The book’s publisher, Paul Dry, the founder of a distinguished eponymously named Indie press, contacted me and suggested a Second Edition so Together could tell the full story of Homer Plessy’s quest for justice, with an epilogue on the pardon titled “The Ultimate Flip on the Script.”

Many years ago, you and I visited the Martin Luther King, Jr. Charter School in the Lower Ninth Ward of New Orleans together, and you organized an oral history project with civil rights leaders in New Orleans. How was that project connected to your work on Together?

We visited the school in March 2011, three months before I saw the article about Keith and Phoebe’s foundation. I had immersed myself in New Orleans civil rights history to prepare for the school visit, focusing mainly on the era of the 1961 Freedom Rides because five local veterans of that protest would be part of the school visit. I hadn’t learned of more recent events, including the work of the Plessy & Ferguson Foundation.

Besides introducing me to New Orleans, there’s another reason the school visited prepped me for wanting to write about the foundation. It reinforced my belief in the value of letting people learn about heroes who may not be super famous, but who still make major contributions and whose stories are inspiring.

My part of the school visit focused on preparing 6th graders for interviews they would do that afternoon with five Freedom Riders we had invited to come to the school. I gave the students strategies for making an interview go well, using as examples interviews I did for my books. The tips included: Do research beforehand on the interviewee, write up a list of questions to use, but also be ready to ask follow-up questions depending on what the person says. I gave students an overview of protest activities the five veterans had participated in. Then we divided the students into five groups so they could write up their list of questions.

In the afternoon, each group interviewed one of these local heroes, taping the conversation. When I transcribed the tapes so the transcripts could be part of that school’s library collection, I was so impressed with the students and also with how open and forthcoming the interviewees were. Those Freedom Riders really wanted young people to understand why they had protested and to encourage them to carry on that important work. The students were an eager audience, totally engaged and enthusiastic.

Later, when I learned about Keith and Phoebe’s foundation, the enthusiasm on both sides of those school visit interviews made me determined to find a way to write about the work Keith and Phoebe were doing. The school visit also gave me a boost of personal courage, to keep persisting in writing about other such heroes.

Not many authors get the chance to revise or update their books. How did you convince your publisher that an update was needed and get the go-ahead for this volume? Your update is more than an epilogue at the end. How did you choose what to update in other chapters and in the backmatter?

Luckily, I didn’t have to lobby for an update. The publisher suggested it! Preparing the Second Edition involved researching and writing the epilogue, while also adding references to the sources and bibliography sections, including a link to a video of the pardon-signing ceremony.

A bit of new information was added to Chapter 4 to clarify the route Homer Plessy’s case took from New Orleans courts to the U.S. Supreme Court. This addition came as a result of a forum that Keith and Phoebe participated in at the Robert H. Jackson Center in upstate New York in September 2022. There, legal expert Gregory L. Peterson shared text from an 1890s letter that researchers found in a New York archive that showed a strategy used by Albion Tourgée, the upstate New York lawyer who gave free legal advice to the New Orleans Citizens’ Committee, the group that had organized the challenge to Louisiana’s train segregation law. The letter showed that Tourgée had suggested trying to persuade Judge John Howard Ferguson to delay setting a trial date if, as expected, he ruled that Homer Plessy could be prosecuted. This delay gave time for Homer Plessy’s New Orleans lawyer to appeal Ferguson’s decision to Louisiana’s Supreme Court. Then, if that court supported Ferguson’s decision, the case could wind up at the U.S. Supreme Court, the Citizens’ Committee’s goal.

What advice would you give writers who want to write nonfiction with a significant oral history component?

Take a look at suggestions listed above that I gave 6th graders for how to do a good interview, which can help authors too: Do research on the interviewee beforehand, write a list of questions, and be ready to ask follow-ups. You also need to win the trust of interviewee. Tell them a little about your experience as a writer and why you’re working on this project, but don’t spend too much time on this. The interview should be about the interviewee, not you. You just want to assure the person that you know what you’re doing.

I explain in advance that I’ll record the conversation and ask if the person is OK with that. If possible, I have the person give permission on the recording. I explain that I’m recording the conversation to be sure to quote the interviewee accurately if I should include quotes from our conversation in the book I’m writing. I promise not to give the tape or transcript to anyone without their permission. I say I’d be glad to send them a transcript of our interview. I also say that if I use any quotes from the interview in the book, I promise to send them the excerpt that includes their quotes before the book is published so they can approve the wording. Often people suggest good re-wordings of the quotes I’ve selected because when they were being interviewed, they were speaking in an impromptu manner. After they see their words in print, they may have nuanced changes to make. Most people don’t make changes, but for those who do, the changes have been good ones.

When I send interviewees their quotes to review, I also send a “Release Form” for them to sign granting permission for their direct quotes to be included in the book. I use regular language in this form, not lawyer-ese, which can scare people away. I also promise on the Release Form that if I include a quote from them in the book, I’ll send them a copy of the book when it is published.

Be sure to follow through and send quoted interviewees a copy of the book. You might mention to your publisher that it’s important to send quoted interviewees a book and maybe that can persuade the publisher to increase the number of free copies they give you. But if you have to buy the books to send out, it’s an expense worth making. A happy interviewee can be one of your best publicists! When you’re invited to give presentations on the book, a happy interviewee may be glad to take part in a panel discussion on the book. It’s a way to lessen the pressure on you, turning you into a panel discussion moderator, not a solo lecturer.

When you finish writing the manuscript, you may not have a publisher yet, which is OK. When you get a publisher, you can tell them you’ve already obtained permission for quotes, which should impress them. The publisher may have a formal lawyer-ese release form they want you to use, but by then, your interviewees are on your side, so they’d probably be OK with signing a more formal release. The Author’s Guild can offer advice on release forms and permissions. If the interview you’re doing is to also to be part of an official oral history collection (such as at a history museum or library), there will be official forms that the organization will want the interviewee to sign; be sure to ask about that.

Writing books that include real quotes from real people, whether famous or not, can help make the story you’re telling come alive for your readers. Write on!

What are you working on next?

I’m working on several projects for different audiences—children, YA, and one for adults—that focus on heroes who may not be “household names,” but have made important contributions in civil rights, science, and music.

*

AMY NATHAN is an award-winning author of more than a dozen nonfiction books for adults and young people, including several on civil rights, among them Together and two on the civil rights history of the Carousel on the National Mall: Round and Round Together, and the picture book co-authored with Sharon Langley, A Ride to Remember. A graduate of Harvard with master’s degrees in education, she has also written books on women’s history for National Geographic, and on music and dance for Oxford University Press and Holt. For more on her books: www.AmyNathanBooks.com.