Monuments and Murals

A few days ago my mother called me to ask about the Black Lives Matter mural in New York City, painted on Fifth Avenue in front of Trump Tower last week. “Can they really do that?” she asked. The bright yellow mural follows ones painted all over the country, including on the street in front of the White House — like the Fifth Avenue mural trolling Trump by taking the message to his front door.

Black Lives Matter marches continue throughout New York City. Most are small and socially distanced, and spread out across the five boroughs to stay safe during the Covid-19 pandemic.

“Can they really do that?” Obviously, the message isn’t going to convince him that Black lives really do matter, that he needs to stop consorting with white supremacists and amplifying their messages and start pursuing police reform and broader racial justice initiatives (as well as initiatives to counter growing inequality in general, as it’s a proven root cause of division, despair, and violence). Rather, it’s an activist’s tool of making the comfortable uncomfortable and highlighting social ills in the hope of changing them. But for people like my mother who came of age during the McCarthy Era, deliberate trolling threatens to release a wave of anger and retaliation on the part of those who hold the levers of power.

Is this a risk we must take? I would say yes, because if those in power are bent on perpetrating injustice and repression, they will do it whether or not we complain. The silent, lonely deaths of now 135,000 Americans hasn’t motivated them to do what’s needed to stop the pandemic, the way most leaders in Asia and Europe have done. As the Covid-19 takes its toll on everyone — but disproportionately on Black and brown people, the elderly, and the disabled, and leaving tens of thousands of newly disabled in its wake — we see more, not fewer, voices speak out against injustice. The police killing of George Floyd sparked the rebellion, but if it weren’t him, it would have been someone else.

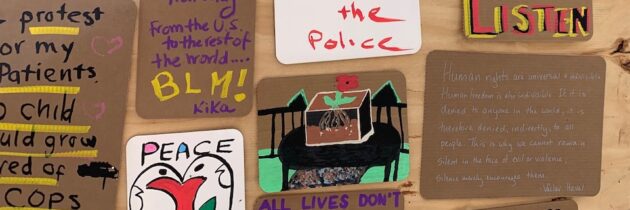

An exhibit of posters in Manhattan to support Black Lives Matter.

Along with painting murals are the toppling of Confederate statues and calls to rename military bases and other sites that have for years carried the names of Confederate generals. Why now after all these years?

Let me offer an analogy. Fifty feet out from a popular beach are dangerous undertows. The town built docks and strung a floating ring between them. They told people not to go beyond the ring and hired lifeguards to make sure people followed the rules. Occasionally, some fool didn’t follow the rules and escaped the ring to swim in the ocean. He (usually a he, but not always) got caught in the undertow and drowned. Over the years, a few more daredevils tried their luck. The town used their tragic deaths as cautionary tales.

Then one summer, the town hired a particularly irresponsible crew of lifeguards. People from all over heard this beach was a big party spot and flocked there. The lifeguards told them to swim outside the ring and even held contests with prizes to see who could swim the farthest and still come back alive. Dozens drowned in the space of two weeks. The town had to close the beach for good. They tore down the docks and put up fences keeping everyone out. No more beach. No more safe swimming area.

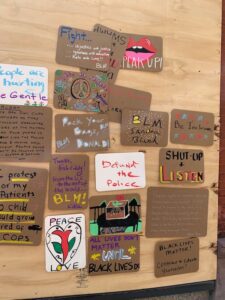

More posters from the exhibit in Manhattan.

When Trump, his family, and his aides amplify the words and praise the actions of violent white supremacists and conspiracy theorists, they’re like the irresponsible lifeguards on the beach. But instead of a few dozen people drowning, they’re pulling an entire nation under water. The Confederate monuments that people maybe resented but left alone now beckon some people to break the rules of a civilized society — one that had abolished slavery, phased out legal Jim Crow, taught the Civil Rights movement in schools, elected a Black president, and while not perfect at least understood the difference between right and wrong and was moving to bend the arc toward justice. Some people, including the police, the “lifeguards,” used those monuments as inspiration to restore Jim Crow and unleash violence on their Black neighbors. So like the beach that had to be closed, the Confederate monuments had to come down.

“But aren’t we erasing history?” you may ask. No. These generals are still in history books. Their statues and images can go into museums, like the photos, statues, and flags of Hitler and other Nazi leaders that fill museums in Germany today, cautionary tales for those who dare forget their history. Books and museums teach history. Statues in public places honor moments in history and the individuals who played leading roles in them. Why would we honor people who owned other human beings, stole their loved ones and their labor, and tortured them to death? The symbols of a barbaric past do not belong on pedestals in the centers of our communities today. Leaving them there glorifies and legitimizes the moral and political universe that those individuals helped to create. It has inspired violent racists, helped to elect some of them to positions of power, and contributed to the situation we face today.

There are other ways to acknowledge a painful past without glorifying it. Public works that serve as vanity projects for dictators often receive new names after their regimes have fallen. For instance, Lisbon’s iconic 25th of April Bridge, which resembles San Francisco’s Golden Gate Bridge and was built by the same company, opened in 1966 as the Salazar Bridge, named for António de Oliveira Salazar, who ruled Portugal with an iron fist beginning in 1926. The bridge kept Salazar’s name for eight years until the Carnation Revolution toppled the regime he established (Salazar himself became incapacitated in 1968 and died in 1970) and ushered in a democratic government that continues to this day.

The date of the Carnation Revolution: April, 25, 1974. Today, the bridge honors not one person but an event that brought freedom and self-determination to the Portuguese people.

The 25th of April Bridge.

At the same time, Salazar’s role has not been erased completely. When the Pilar 7 bridge museum opened two years ago, I took a tour of the structure that included a short, informative film about its construction. The film concludes with the replacement of the dictator’s name shortly after the April 25th revolution. While the film acknowledges the role Salazar and his regime played in expanding public works in Portugal from the 1940s through the 1960s, one can also see why the arrival of democracy in Portugal led to removing his name. As the country’s economy grew and flourished in the 1980s and 1990s, the bridge, too, has been expanded, with wider lanes and a lower level added for rail traffic. This experience of change and improvement, both physical and political, can offer a teachable moment about the naming of monuments and how a society replaces or adapts monuments over time. It can show how people address a troubled past as they seek a more just future.