“Not Like the Other Girls”

As this month is Women’s History Month, it’s a great opportunity to take on one of the most common tropes in fiction for tweens and teens. The “Not Like the Other Girls” trope involves a girl protagonist who considers herself different from her peers in that she cares about more serious issues than appearance, fashion, boys, and celebrities. While it’s meant as a critique of traditional gender roles and pursuits — after all, the protagonist is rebelling against them — it assumes that all the other girls are shallow underachievers. Besides this demeaning assumption about the novels’ female secondary and tertiary characters, the trope feeds into the antifeminist Queen Bee, the only woman among men in a position of authority who manages to knock down any other woman who dares to rise to her level. The bright high achiever in school and sport who consider themselves “not like the other girls” are not looking deeper for the talents of the other girls or giving the other girls a chance to shine.

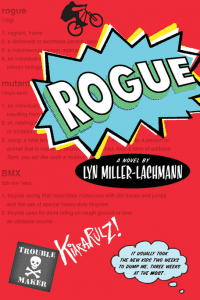

I admit that I’ve struggled with and fallen prey to this trope. Growing up, I was not like the other girls, but I didn’t consider it much of an asset — or if it did, it was justifying to myself that I didn’t have friends and wasn’t getting invited to parties because I was more intelligent and serious than they were. This justification covered up the fact that most of the time I felt different and “less than,” something I’ve come to understand since my diagnosis on the autism spectrum as an adult. In writing my Rogue protagonist Kiara, who doesn’t have any girl friends and mostly hangs out with boys, I drew on my own experiences in middle and high school but never resolved what it meant for her not to have friends of her own gender or to attempt such a friendship beyond trying to become popular by sitting at the popular girls’ table. My protagonist of Surviving Santiago, Tina, was also isolated from girls her own age, though not by choice, when she was forced to spend her summer with her father in Chile after her parents’ divorce and her mother’s remarriage. Lída, the only girl protagonist along with three boys in Torch, is also isolated from her girl peers due to her frequent moves. Her lone friendship with a girl classmate who is Roma ends in her betraying her friend in order to attract a boy’s attention, an act she deeply regrets and one that motivates her to help a younger girl in trouble later on in the novel.

I admit that I’ve struggled with and fallen prey to this trope. Growing up, I was not like the other girls, but I didn’t consider it much of an asset — or if it did, it was justifying to myself that I didn’t have friends and wasn’t getting invited to parties because I was more intelligent and serious than they were. This justification covered up the fact that most of the time I felt different and “less than,” something I’ve come to understand since my diagnosis on the autism spectrum as an adult. In writing my Rogue protagonist Kiara, who doesn’t have any girl friends and mostly hangs out with boys, I drew on my own experiences in middle and high school but never resolved what it meant for her not to have friends of her own gender or to attempt such a friendship beyond trying to become popular by sitting at the popular girls’ table. My protagonist of Surviving Santiago, Tina, was also isolated from girls her own age, though not by choice, when she was forced to spend her summer with her father in Chile after her parents’ divorce and her mother’s remarriage. Lída, the only girl protagonist along with three boys in Torch, is also isolated from her girl peers due to her frequent moves. Her lone friendship with a girl classmate who is Roma ends in her betraying her friend in order to attract a boy’s attention, an act she deeply regrets and one that motivates her to help a younger girl in trouble later on in the novel.

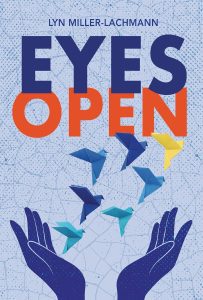

In my forthcoming Eyes Open, I found I needed to address this trope head-on. It was my first book since Rogue and Surviving Santiago that featured a girl as a sole protagonist. (In Gringolandia, Moonwalking, and Torch, boys comprise most if not all of the POV characters.) Sónia is not autistic; nor has travel or frequent moves separated her from her peers. She attends an all-girls’ school, labors among other women and girls in a hotel laundry facility, and is the second of five daughters in her family. Not having spent a lot of time with girls my own age growing up, I found this book challenging, but I also benefited from the insights of my daughter and the women in Portugal who I’ve befriended as an adult as well as those I interviewed for the novel.

Sónia does care about appearance and fashion, she follows pop music (some of it banned), and she’s boy-crazy to the detriment sometimes of her friendships with girls. Like Lída, she betrays a friend to attract a boy, and another friend betrays her to the same end. Beneath this superficial exterior, though, she thinks deeply about poetry, free will, and her purpose in life. And so do her friends and her sisters.

In writing Eyes Open, I realized that the alternative to the “not like the other girls” trope is to give depth and complexity to all the girls, as well as to the relationships among them. Yes, Sónia writes poetry to her boyfriend in prison and in it, criticizes a regime that turns everyone except the elite into second class citizens, and women into third class citizens. But she starts the Poetry Club with her best friend Nídia, and it turns out to be one of the most popular clubs in her all-girls’ school. She fights with her sisters and notes that her grades are higher than older sister Mariana’s, but she also sees where her sisters are smarter than she is, and in the end one sister, a most unlikely ally, basically saves her life as they work together toward their biggest, most unattainable goal. I don’t want to spoil anything, but I believe that middle sister Carolina is the smartest of all. I see the two key principles to challenging the “not like the other girls” trope as humility and solidarity. Humility in the protagonist acknowledging that she is not special, chosen, or better than her female peers. Solidarity in working with her peers to make all their lives better.

In writing Eyes Open, I realized that the alternative to the “not like the other girls” trope is to give depth and complexity to all the girls, as well as to the relationships among them. Yes, Sónia writes poetry to her boyfriend in prison and in it, criticizes a regime that turns everyone except the elite into second class citizens, and women into third class citizens. But she starts the Poetry Club with her best friend Nídia, and it turns out to be one of the most popular clubs in her all-girls’ school. She fights with her sisters and notes that her grades are higher than older sister Mariana’s, but she also sees where her sisters are smarter than she is, and in the end one sister, a most unlikely ally, basically saves her life as they work together toward their biggest, most unattainable goal. I don’t want to spoil anything, but I believe that middle sister Carolina is the smartest of all. I see the two key principles to challenging the “not like the other girls” trope as humility and solidarity. Humility in the protagonist acknowledging that she is not special, chosen, or better than her female peers. Solidarity in working with her peers to make all their lives better.

Lyn, this is a really thought-provoking post. I appreciate you tackling the subject here and in your book. Growing up, I “wasn’t like other girls” either in that I enjoyed reading science fiction and fantasy books. Even today, whenever I see reviews about the viewership of movies like Dune and Dune 2, we’re told that population skewed male. I grew up reading science fiction and watching it with my dad. So many women write science fiction now. So glad to see that.

I’m glad you mentioned humility. I really appreciate that.

The media are often the last to know. For instance, there was a longstanding belief that LEGO builders were almost always male, but a third of the members of my LEGO User Group in NYC in the 2010s were women. Now we learn that women aged 40-65 building for themselves are the fastest growing segment of LEGO purchasers, and new sets like Botanicals and Mosaics are reflecting that. Which reminds me — I am long overdue for a Little Brick Township update!