PEN World Voices Festival 2018: “What Shall We Tell the Children?”

The PEN World Voices Festival has ended, the staff are taking a well-deserved rest, and once again, I RSVP’ed for a hot-ticket closing reception and bailed at the last minute. On Saturday, the day before the festival ended, I attended the panel sponsored by the PEN Children’s Committee, which grew out of a discussion from one of our meetings last fall: As authors and as caregivers and teachers, what do we tell the children about the current political situation?

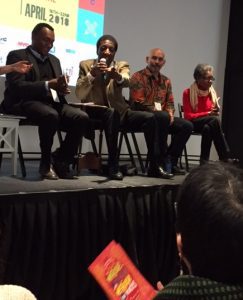

Fatima Shaik moderated the panel, from left, Eric Velasquez, Wade Hudson, Innosanto Nagara, and Tonya Bolden.

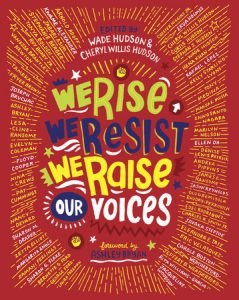

With PEN Children’s Committee co-chair Fatima Shaik moderating, the panel consisted of contributors to a new volume of poetry, essays, and art for children coming out from Random House this September, We Rise, We Resist, We Raise Our Voices, edited by Just Us Books’ co-founders Wade Hudson and Cheryl Willis Hudson. The four panelists were editor Wade Hudson, writer Tonya Bolden, and visual artists Innosanto Nagara and Eric Velasquez. (Another writer with a poem in the collection, Zetta Elliott, spoke on a different panel the night before.)

Rather than begin with opening statements, Shaik posed the first question: What are kids hearing about the current situation? What should they know and not know? The panelists spoke from their perspectives as children growing up Black in Louisiana and South Carolina in the 1950s (Hudson and Bolden, respectively), needing to know about their oppressive circumstances in order to survive; as Puerto Rican in Harlem in the 1960s, awakening to the truth and to the possibility of making change (Velasquez); and in Indonesia in the 1970s, with parents who spoke out openly against that country’s military dictatorship (Nagara). The panelists agreed that one tells children different things at different ages, but Nagara observed the same kind of fear and trauma among schoolchildren after the 2016 election that he remembered from his childhood in Indonesia — children crying in the classroom and worried about what will happen to their parents. As a parent of school-aged children as well as an activist, Nagara said that we cannot promise children that everything will be OK, but we can give them the tools to cope. Bolden recalled growing up in South Carolina, at a time when the country wasn’t a safe place either, but she also remembers the good times of working together with family and community, cooking dinner or doing laundry, and cited family and community bonds in the past as a way people coped with fear and oppression.

Wade Hudson urged parents to spend time with their children rather than preaching at them from on high or disengaging altogether.

Shaik then asked: How much should children be disturbed? The panelists agreed that there is too much vulgarity in our society and that acceptance of vulgarity allowed a TV reality show host with a limited vocabulary and a history of immoral behavior to win the election. Bolden pointed out that vulgarity comes from not having language and critical thinking skills. (After listening to the panel, I went home and removed nearly all the curse words from my work-in-progress, because my characters have developed those skills.) Hudson urged parents to spend time with their children rather than preaching at them from on high or disengaging altogether. The panelists then discussed some of the constraints to spending time with children, notably the fact that so many parents work multiple jobs to survive. Bolden remembered the “children’s table” of earlier times, which prevented children from being exposed to too many adult subjects before they were ready to handle them. Hudson responded that well-chosen books are a good way of introducing unfamiliar or difficult topics in an age-appropriate manner.

The next question focused on illustration and how illustrators show social justice. Velasquez talked about bringing dignity to his characters, using illustrations from his picture book biography of Cuban-born scholar Arturo Schomburg and how he arrived in New York City with his head high and his posture perfect, ready to conquer the world. Nagara said he considers his audience and how his images would appear to a variety of readers — those who share the culture and those who may be coming to it for the first time. He, like Zetta Elliott the day before, discussed Rudine Sims’s concept of mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors.

Shaik then asked: Do you tell Black children the same thing you tell white children? Bolden, who mainly writes nonfiction, said “there’s only one story, the truth.” Hudson said that it’s important to have conversations with children after they read a book.

Since many of the panelists have written or illustrated books about people who challenge authority, Shaik wondered how to teach respect for authority when the police brutalize people of color. Velasquez said that one cannot be a silent bystander, just like one cannot be a silent bystander to schoolyard bullying. Bolden’s parents taught her to obey illegitimate authority for self-protection. She cited Martin Luther King, Jr. as someone who challenged authority in a respectful manner. Nagara learned early on to “respect people and challenge authority, but to keep safe as well.” His most recent book, The Wedding Portrait, explores the right and wrong contexts to challenge authority. “It’s all about context,” he said.

The final moderator question had to do with censorship, a topic of great importance to the Children’s Committee and to PEN in general. The panelists spoke mainly about the internet and social media, but Nagara pointed out that TV brought inappropriate messages to children long before the internet. Velasquez urged adults to model the behavior they wanted to see in children, including not spending family time looking at the smartphone. Hudson said that rather than blame electronic media, we need to look at how we got to where we are in terms of the breakdown of other social institutions.

The audience members also had questions. One father asked the panelists how to handle family members who did not see the world in the same way, who dehumanized people who were different. Bolden nostalgically mentioned the children’s table. Nagara pointed out that different perspectives and problematic perspectives are part of life; children shouldn’t be shielded completely because they may be hearing the same things in the schoolyard. Hudson compared the racist uncle to the alcoholic uncle. I found this to be a useful comparison, and so did the person who asked the question.

A second parent asked how to talk to young children about privilege. Bolden urged families to work with those who don’t have privilege. Nagara reminded the audience that these aren’t on-off conversations but ones that continue throughout childhood and adolescence. Shaik pointed out that “we are all privileged in some ways but not privileged in others.” Have children think about times when they haven’t been good at something or have been excluded. Velasquez reminded us of the importance of books and stories.

A second parent asked how to talk to young children about privilege. Bolden urged families to work with those who don’t have privilege. Nagara reminded the audience that these aren’t on-off conversations but ones that continue throughout childhood and adolescence. Shaik pointed out that “we are all privileged in some ways but not privileged in others.” Have children think about times when they haven’t been good at something or have been excluded. Velasquez reminded us of the importance of books and stories.

The final question wrapped around to the first: How do we have these conversations without instilling fear in children? Nagara said that if we don’t have the conversations, children will hear from somewhere else. And they will be likely to end up more fearful than ever. Bolden recommended informational books as a way of showing children and adults who faced and conquered fear. Hudson and Nagara cited two resources, the Teaching Tolerance website and Raising Race Conscious Children.

Most of the 40 audience members were parents and educators, and they very much appreciated this advice from authors and illustrators who recalled their own childhoods in politically perilous times and who had the experience of being parents and grandparents themselves. The “What Do We Tell the Children?” panel was a bit different from most World Voices panels in that, rather than discussing freedom of expression and today’s political events, it offered practical advice and resources for parenting in a challenging (and rapidly changing) era of our country’s history.

Thanks for the good reporting, Lyn. Glad to have your blog bookmarked. And I am sending your fabulous leggo creation to my 7 year old autistic grandson

Thank you, Emily! I’m glad you found the piece helpful! And I’m now working on a Lego houseboat, but it will have to wait until I return from Portugal to finish. I hope your grandson enjoys the pictures and finds inspiration for his own creations!

“What are kids hearing about the current situation? What should they know and not know?”–Such great questions. I can’t help thinking of parents during a time of war who were faced with raising children during a turbulent time. Thank you for summarizing this festival.

I’m glad you liked the piece. I happen to be translating a middle grade novel now about a child living through war, and the author does a very good job of presenting it in an age-appropriate way.