Rattling the Cage for Ukraine

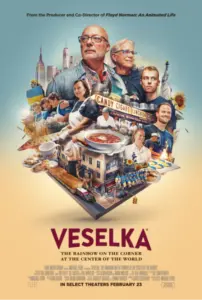

Yesterday evening I attended a screening of a new documentary film about a favorite local gathering place, Veselka: The Rainbow on the Corner at the Center of the World, followed by a Q&A with the director and several of the people featured in the film. On the third day after the official premiere, the showing was sold out, demonstrating the role of word of mouth in sustaining an audience.

Originally conceived as a portrait of a family business adapting to changing times in the neighborhood, New York City, and the country — from the escape of Volodymyr Darmochwal and his young family following the Soviet takeover of western Ukraine at the end of World War II through the decline of the Little Ukraine neighborhood in the crime-filled 1970s and 1980s to the Covid-19 shutdowns of restaurants in 2020 — the focus of director Michael Fiore’s project changed after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. After Volodymyr’s sudden death in 1974, the little Ukrainian newsstand and coffee shop he started on the corner of Second Avenue and East Ninth Street passed on to his non-Ukrainian son-in-law Tom Birchard, who promised to keep the family’s traditions alive. Tom kept his promise beautifully. His son Jason Birchard attended Ukrainian language school growing up and now speaks the language (though with a bit of an accent for which he apologizes). Jason took over the restaurant around the time of the pandemic and has led its planned expansion along with his nephew Justin. But the emphasis is less on the transition (the original plan) and more on how Veselka became a lifeline for its Ukrainian employees and the wider community as they try to support their families and friends faced with conquest and extermination at the hands of Russian dictator Vladimir Putin.

Originally conceived as a portrait of a family business adapting to changing times in the neighborhood, New York City, and the country — from the escape of Volodymyr Darmochwal and his young family following the Soviet takeover of western Ukraine at the end of World War II through the decline of the Little Ukraine neighborhood in the crime-filled 1970s and 1980s to the Covid-19 shutdowns of restaurants in 2020 — the focus of director Michael Fiore’s project changed after the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine on February 24, 2022. After Volodymyr’s sudden death in 1974, the little Ukrainian newsstand and coffee shop he started on the corner of Second Avenue and East Ninth Street passed on to his non-Ukrainian son-in-law Tom Birchard, who promised to keep the family’s traditions alive. Tom kept his promise beautifully. His son Jason Birchard attended Ukrainian language school growing up and now speaks the language (though with a bit of an accent for which he apologizes). Jason took over the restaurant around the time of the pandemic and has led its planned expansion along with his nephew Justin. But the emphasis is less on the transition (the original plan) and more on how Veselka became a lifeline for its Ukrainian employees and the wider community as they try to support their families and friends faced with conquest and extermination at the hands of Russian dictator Vladimir Putin.

Panel discussion after the film included (from left) director Michael Fiore, Jason Birchard, Tom Birchard, and Veselka staffer Dima.

Two of Veselka’s longtime employees, Dima and Vitalii, had parents and other relatives trapped in Ukraine. Dima’s aunt and uncle lived under Russian occupation and had to escape before the Russians deported them to gulags deep inside Russia — a fate that happened to the father of one of the restaurant’s Ukrainian visitors. Since the beginning of the war, Jason has helped more than a dozen Ukrainians to safety in the United States. His young employees have lost friends in the war and considered returning to Ukraine to fight, but they know that if they went back and were killed, their families would not be able to find new homes following a potential Russian takeover of the country.

The release of the Veselka documentary was timed for the second anniversary of the war. This is a desperate time for Ukraine because the Trump-aligned leadership of the U.S. House of Representatives has refused to bring to a vote an aid bill for Ukraine that passed the Senate with a bipartisan majority of 70-29. Trump himself has voiced his support for Putin, and the House leadership, beholden to him, plans to deliver the country up to the brutal Russian regime, which recently succeeded in eliminating its most popular critic Alexei Navalny by killing him in prison. House Speaker Mike Johnson, who comes from the Louisiana district where my mother grew up, claims he is a Christian, but by taking the side of Putin in a conflict that shows one of the most clear distinctions between Good and Evil — I’d be hard pressed to find a greater embodiment of Evil than Vladimir Putin — Johnson shows that he really doesn’t understand the distinction between or care about what’s right and wrong. This is not a time for either hypocrisy or moral relativism. Innocent people are suffering and dying because of the actions of one man and his brainwashed or terrified people.

The film doesn’t end with a call to action — one of the issues people in the Q&A pointed out — but I’m issuing one. Ukraine is running out of ammunition — ammunition only the U.S. produces — and will not have more unless this bill is passed. Without ammunition, the country will have to surrender to Putin, who has no incentive at this point to settle for part of Ukraine’s territory. He wants it all, and without weapons and ammunition, Ukraine cannot stop him. If that happens, the remaining cities will be bombed to dust, and all of the equipment already handed over to Ukraine will either be destroyed or become Russian property to be turned against the rest of Europe. These are the geopolitical stakes, along with the message it sends to China about Taiwan and the rest of Europe about where the U.S. stands.

There are also the humanitarian stakes — a nation of 43 million people faced with conquest, the destruction of their culture and language, and physical extermination. Already, Russia has deported millions of Ukrainians to the far east and north — the strategy they’ve used against recalcitrant populations from the Chechens and Crimean Tatars to the resistance fighters of Hungary, Poland, ad the Baltics. (One of the most powerful exhibits in Budapest’s House of Terror museum is a giant room with a floor map showing where the Hungarian anticommunists were taken in Siberia, many of them never to return.) Knowing the difference between right and wrong means siding with people who were just trying to live their lives and not hurting others like the Ukrainians before the invasion, rather than with those committing atrocities against them.

My friend Linda Elovitz Marshall celebrated the launch of her picture book biography Brave Volodymyr at Veselka last fall.

So here’s my call to action. One: Wherever you live, contact your Congressional representative and ask them to sign the discharge petition to bring the Ukraine aid to the floor. Be loud, especially if yours is one who has been soft on Putin and his imperialistic aims. Two: Donate to one of the organizations helping the Ukrainian people during this difficult time (list here). Three: See the film, or if it’s not in theaters where you are, contact your streaming service about carrying it. Veselka is worth seeing, as it shows the place of this favorite restaurant in the community as well as the impact of the war. Four: Spread the word through your own social media or other channels about Ukraine’s need for support and about this film. And remember, freedom isn’t free. It depends on all of us working together and supporting each other.

Update 10/24: The Velselka documentary is now available from various streaming services as well as on Blu-Ray. Congratulations to the filmmakers for getting both online distribution and physical copies! Viewers are in for a treat!

Update 10/24: The Velselka documentary is now available from various streaming services as well as on Blu-Ray. Congratulations to the filmmakers for getting both online distribution and physical copies! Viewers are in for a treat!

Thank you for this galvanizing post. I have contacted my representative in the House.

When/if the Veselka movie becomes available to stream online, I would love to know so I can both view overseas and share.

Thank you for contacting your representative about the need to help Ukraine (and the rest of Europe) against Russian aggression. I’ll let you know if I hear anything about streaming availability for the movie. I think it will have broad appeal, between the owners’ family story, the race to get the two staffers’ mothers out of Ukraine, and their adjustment to a new life in NYC. As I watched the film, I thought of my late husband’s family members who escaped Germany in the 1930s and how they were judged on whether they were able to save their mothers from the Nazis.

I would love to learn the details of how Volodymyr and Olha Darmochwal were able to flee the Soviet Union after the war. No Soviet Union citizens were allowed to cross the border. Some Ukrainians were forced into labor camps in Germany during the II World War, and some Ukrainians fled the Soviet Union at the end of the war along with Nazis if they collaborated.

Thanks for commenting, Julia! The film didn’t cover the circumstances under which the Darmochwal family arrived in New York City in 1947, but many of the people who came to the U.S. from Eastern Europe in the years after the war were from displaced persons camps. The region of Ukraine from which they came was part of pre-war Poland, and when Poland’s borders were moved further west, many people — mostly Polish but some Ukrainians — journeyed west as well. For Instance, I researched the life of Solidarity co-founder Anna Walentynowicz, who was ethnic Ukrainian from near Równe, Poland, now Rivne, Ukraine. After the war, in which she’d lost her entire family, she migrated to Gdánsk with a Polish family for whom she worked. In any case, a book that explores the complexities of the time and the massive post-war migration is Ola Hnatiuk’s Courage and Fear: Non Heroic Narratives of Occupied Lwów, which I write about here.

.