Redemption: The Ugly History of a Word

I don’t think the current president knows the meaning of all the words he uses, but his advisers and speechwriters do. So when he used the word “redemption” at a MAGA rally in New Hampshire on the eve of the primary earlier this month, a lot of people wondered why and what it meant. He raised it in the context of the border wall, telling his audience

“You do know who’s paying for the wall, don’t you? Redemption from illegal aliens that are coming. The redemption money is paying for the wall.”

Shortly after taking power, the president floated the idea of seizing portions of wire transfers from immigrants, documented and undocumented, to their families abroad. These are known as “remittances” and have long supported immigrants’ families and communities back home. Such remittances from their families abroad kept Irish peasants alive during the nineteenth century Potato Famine as well as members of my own family who struggled to make a living and eventually sought passage out of Eastern Europe at the turn of the twentieth century. (Had they remained in their homes rather than moving to the U.S. or Argentina, they surely would have perished in the Holocaust.) The president didn’t get to take the remittances, thereby leaving taxpayers to fund the wall, because so far in this country, a leader cannot just snap his fingers and deprive anyone of their assets and property without due process. Yes, these things can happen (google “civil asset forfeiture”), but those deprived of their money and property can sue to get it back and several municipalities have been exposed for their arbitrary and corrupt seizures of property.

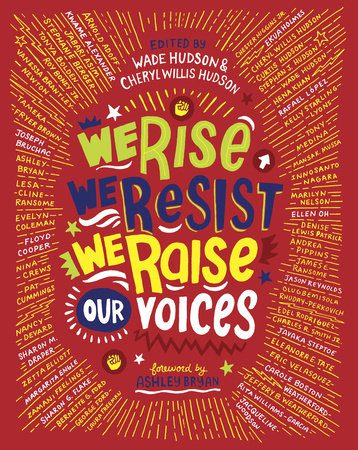

This collection, published in 2018, is a powerful tribute to those who stood up for freedom, from the founding of the Republic through the Civil Rights Movement to the present.

In fact, the rally-promised redemption is related to the seizure of remittances as well as the seizure of a whole lot more. And here, in the middle of Black History Month, let us turn to the years after the Civil War, when the victorious Union government proclaimed the freedom of enslaved people and ratified the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution outlawing slavery, granting citizenship and its associated rights to all persons, and allowing all African-American men to vote (as women didn’t gain the franchise until the 19th Amendment in 1920). Plantation owners who supported the Confederacy lost their land, much of which was granted in small parcels to the formerly enslaved people who had actually worked that land. With the right to vote, African Americans elected leaders, and because the fruits of their labor didn’t go to someone else by law, they could get an education, start businesses, enter professions, and become wealthy — the promise of a market economy which before really wasn’t a market economy as long as human beings were treated as livestock on the basis of their skin color. Throughout the South, thriving Black communities showed what work ethic and ingenuity could do when people lived in freedom.

But the Southern slavocracy, vanquished on the battlefield, lay in wait. They knew that if they stuck together, they could outlast the will of the federal government to guarantee the safety and freedom of Black communities. They knew that in the corrupt patronage system that characterized the federal government at that time, Republican leaders cared more about their own jobs and fiefdoms than about defending the new amendments to the Constitution that guaranteed equal treatment under the law to all Americans. The Compromise of 1877 gave the presidency to the Republicans in return for pulling federal troops out of the South, thus allowing the Redemption.

Barbara Wright’s CROW is a powerful read set in Wilmington at the time of the 1898 race riot and coup that brought a Jim Crow regime to that city.

Over the next two decades, the Redemption involved the seizure, by law and by violence, the farms, businesses, and other assets of Black Americans, the deprivation of voting rights, terrorist killings, mass incarceration, and the imposition of Jim Crow — a racial caste system that devastated Black political power and economic opportunity in the South. Many African Americans responded by leaving their homes, traveling west and north in what became the Great Migration.

When I took history in middle and high school in Houston, Texas, I learned nothing about the Redemption, even though the ill-gotten gains from seizing African-American assets, and the ill-gotten opportunities from locking out people based on the color of their skin, flowed to my immigrant family as well as the families of my classmates descended from enslavers. We talk about reparations for slavery, but, having grown up in the South, I think there should be additional reparations for Jim Crow — for the lives lost, the property seized, the educational and economic opportunities taken away. It’s a stain upon the country that, unresolved like everything else about white privilege, echoes in the present day threatening to upend the Constitution, the rule of law, and the promise of both democracy and a free-market economy.

So when the president uses the word redemption in the context of seizing assets of a group based on their immigration status, national origin, religion, or skin color, it is not an accident, and it is not a joke.

Reading this article, I recall the land and livelihood stolen from Native Americans after decade after decade of broken promises.

I remember families from far away states that lost fathers, sons, brothers in the Civil War though they had never seen a black person. Many believed in equality- no matter what the government’s actual reasons for fighting a Civil War.

I recall the failure of our government to keep farmers and their families from starvation during the Great Depression of the late 1800s. I think about Washington DC’s willingness to foreclose on homesteads of Americans whose crops were destroyed by locusts and drought.

I remember the humiliation of Coxey’s Army, perhaps the first march on Washington by unemployed from across the country.

I think of Japanese American internment camps.

So much suffering and death of innocents.

Read “Prairie Fires” by Carolyn Fraser- a biography of Laura Ingalls Wilder and the stoic Midwestern world she inhabited. The story offers a stunning portrait of government cruelty, ignorance and denial of white folk in the North.

Read this book and then reconsider White privilege. We all come from somewhere and that somewhere isn’t always sweets and feather beds.

What are we doing today to make certain government won’t make the same mistakes: use the military for ill-begotten cause, cage children, steal privilege from anyone?

Will the United States going bankrupt with reparations for all the injustices listed above -and those not listed- make us a stronger, kinder nation or will it merely extend the hatred, neighbor by neighbor?

The U.S. did pay reparations for the internment camps, $20,000 per survivor, which Ronald Reagan signed into law in 1988. While it didn’t cover the families’ losses and came 40 years later, it represented an acknowledgement that what the government did to the Japanese Americans during World War II was wrong, and it set a precedent for legal claims in the future when the government targets a single group, taking away people’s freedom and everything they’ve worked for. I think people need to realize that a government that strips the freedom, dignity, and resources of one group is eventually going to come for them.

Well said!

Thank you! Jamelle Bouie’s column is good too, in showing that we shouldn’t just point to what’s going on in Russia, Turkey, and Hungary but to our own history and specifically to the Southern states.