The 2016 Brooklyn Book Festival: Historical Fiction for Kids and the Value of Small Presses

I had only planned to spend the morning and early afternoon at the Brooklyn Book Festival, checking out the publishers’ and community organizations’ booths in between a 10 am “PEN Presents: Won’t Know Much About History” panel on diverse historical picture books and middle grade fiction and my Q & A on translated books for children at the SCBWI booth at 1 pm. However, I ended up staying until the end, as the microphones were collected and the booths packed up. There were too many great people to talk with and things to see.

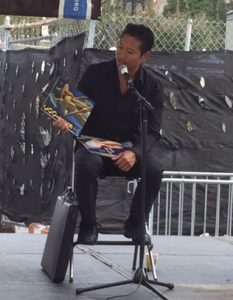

The “Won’t Know Much About History” panel at the 2016 Brooklyn Book Festival. From left, Fatima Shaik, Sharon Dennis Wyeth, Jeanette Winter, Chris Soentpiet, Sean Qualls.

Worried about transit disruptions after the previous night’s bombing incident in Manhattan (a block and a half away from my son’s apartment, though he was elsewhere at the time), I arrived early and met the managing editor of Curbside Splendor, a small press that published a pair of outstanding young adult novels I reviewed for The Pirate Tree, Erika Wurth’s Crazy Horse’s Girlfriend and Chris L. Terry’s Zero Fade. Both of these books were included in the We’re the People 2015 Summer Reading List of recommended books for children and teens by writers of color.

Steps away from the booth was the panel, moderated by PEN Children’s Committee co-chair Fatima Shaik, that included illustrators Sean Qualls and Chris Soentpiet and authors Sharon Dennis Wyeth and Jeanette Winter. Shaik began the discussion with questions on why the authors and illustrators chose the genre of historical fiction. Wyeth led off, talking about growing up in the mostly-black Washington, DC, neighborhood of Anacostia and wondering why her skin was lighter than most of her peers’. This led her into an exploration of slavery, but when she chose to write a novel, it meant starting with the experience of the individual. She pointed out that history textbooks don’t present the stories of individuals and how they were affected by the events of their times. That is what historical fiction offers.

Winter started out writing historical nonfiction. Her debut book, in 1988, was Follow the Drinking Gourd, about the Underground Railroad. Even then, she felt that, as an outsider, she needed someone to vet the book, and Virginia Hamilton helped her with it. Winter said that the story needs to grab her for her to write about it. Soentpiet talked about being fascinated with the costumes, people, and stories of the past. As a visual person, he was first drawn to what people wore and the important objects of their lives.

Qualls laughed at the history question because it seemed to be his least favorite subject in school. (If you’re Sean Qualls’s former social studies teacher and you’re reading this, he says you’ll be shocked.) But he was drawn to stories that haven’t been represented or have been misrepresented, and he gave the example of the memoir of Josiah Henson, which Harriet Beecher Stowe appropriated and turned into the character of Uncle Tom. In fact, Henson was a community leader who, after escaping slavery and helping other to escape, organized a black settlement in Canada.

The second question addressed the research process. All of the panelists talked about visiting museums and historical societies and talking to the people there. Some started creating books before the age of the internet, but all of them reaffirmed that the internet is not enough.

As PEN is dedicated to the fight against censorship, much of the panel focused on how to deal with difficult material in a way that is true to the history, children can understand, and is not too depressing or frightening. Winter said that all of her books end on a note of hope (except for one nature book in which the polar bears do not survive). She also cited Emily Dickinson’s advice to “tell the truth but tell it slant.” This approach allows readers of different ages to appreciate the book on different levels.

Wyeth commented that slavery is an especially difficult topic to write about for young reader. In Corey’s Underground Railroad Diary, part of Scholastic’s My America series for young middle grade readers, she gave Corey interests that many children share. She agonized over a scene in which Corey breaks a dish and the slaver wife hits him in the eye with a metal key. This motivates his family to escape and shows readers the importance of not accepting abuse. Soentpiet also stressed the importance of not showing children as victims.

Winter talked about the banning of one of her books, Nasreen’s Secret School, because some people saw words in Arabic or mentioning “Allah” (“God” in Arabic) and believed she was trying to convert children to Islam. She was surprised because she had been careful and even-handed but it’s hard to predict what some people will find objectionable.

A final question from the moderator had to do with authenticity and whether a person has to be part of a culture to write about it. Wyeth observed that with historical fiction, “we weren’t alive” and it’s important for any writer to identify the human qualities that never change and put those into the historical circumstances. She was able to do this when she researched her family background. Soentpiet talked about starting out illustrating only Asian-American stories (he’s of Korean heritage, adopted by a white family), but since then he has come to illustrate a variety of scenes. His ability to humanize each character drew the attention of Christine King Farris, whose memoir My Brother Martin he illustrated. Qualls stressed the importance of having many representations; the problem is when the outsider’s book is the only story. In all, Shaik said, the problem is as much an economic problem as a creative one — making sure book creators of all backgrounds have a chance to be published with the same level of support, as much as making sure all of the representations are authentic.

Panelists pose at the end of the event. From left, Fatima Shaik, Chris Soentpiet, Sharon Dennis Wyeth, Sean Qualls, Jeanette Winter.

So what happens if someone “gets it wrong,” as many have done recently (not only outsiders but in the case of A Birthday Cake for George Washington, a team of insiders)? Qualls said that bad representations are great for conversation as long as they’re not openly hurtful, and Wyeth agreed. She said that authors have to care about their readers and look at why a particular bad representation is hurtful or problematic. She brings her research materials to schools and talks about the writing process, and she said that more authors and illustrators have to go to schools and engage directly with readers. She and Soentpiet also emphasized the importance of author’s and illustrator’s notes; every historical book for children should have them.

An audience member asked about how historical fiction sheds light on the present, and Wyeth added another dimension to that statement, as she talked about how her personal situation — aspects of her family relationships — drove her to investigate events that occurred generations before her. Her research allowed her to understand hardships of her mother’s childhood and her grandfather’s desire to fight in World War I. She realized in the course of her research that her ancestors would not have been able to see the popular films of the 1910s because of Jim Crow. They were not allowed into their town’s only theater. And, of course, Netflix didn’t exist.

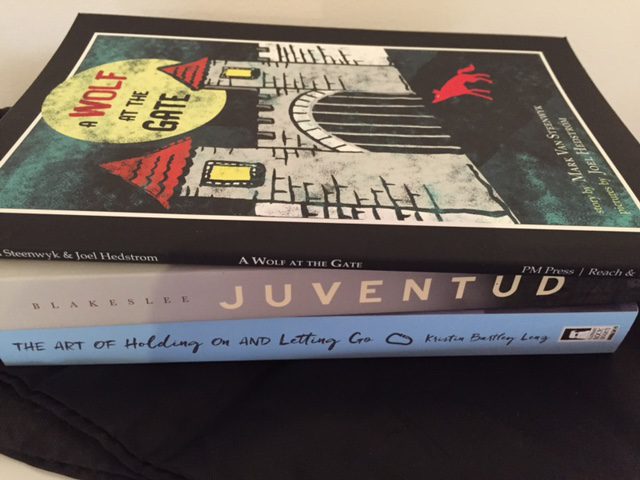

New books from small presses at the Brooklyn Book Festival: A Wolf at the Gate (Reach and Teach), Juventud (Curbside Splendor), The Art of Holding On and Letting Go (Elephant Rock Books).

After this excellent panel, I made my way through the booths and in addition to Curbside Splendor picked up new titles from Elephant Rock Books (publisher of the acclaimed The Carnival at Bray by Jessie Ann Foley) and Reach and Teach (publisher of the YA novel Abe in Arms by Pegi Deitz Shea and the picture book Operation Marriage, one of Bluestockings’ best sellers by Cynthia Chin-Lee and Lea Lyon). I also met up with Selene Castrovilla, a traditionally published author of historical picture books set in the 18th century and an indie-published author of the gritty and gripping YA romance series that began with Melt and continues with Signs of Life, and got to know a brand-new YA publisher from Brooklyn, Across the Margins. At the Across the Margins booth, I spoke to the co-founder and offered advice on preparing ARCs so the publisher’s forthcoming titles are considered for trade reviews that are so important to getting into libraries and schools. I hope they prosper because I suspect in the next few years, we’ll need small presses — especially progressive ones and ones committed to diversity — more than ever.