The Problem With Ableist Language

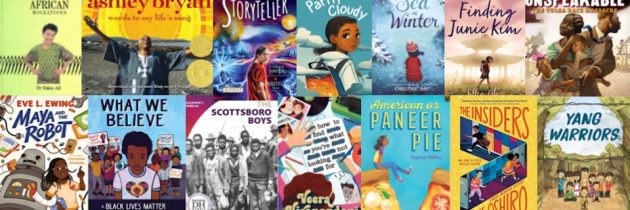

Last weekend I typed “END” on the draft of EYES OPEN and sent it to my agent to look over before its March 1 due date with my editor. While I wait for her to weigh in, I’m reading books for the 2023 We Are Kid Lit summer reading list. This year’s list represents a collaboration with School Library Journal, which has expanded its relationships with book bloggers to support diverse perspectives in children’s literature. Our collaboration also means that a “teaser list” of up to five books in each category (picture books, chapter books, middle grade, YA, and YA/adult crossover books) will appear at the end of March, with the full list published in May.

Our mission statement that precedes the list reads as follows:

Are you looking for a curated summer reading list that celebrates diversity, inclusivity and intersecting identities? The We Are Kid Lit Collective selects books by and about BIPOC (Black, Indigenous and People of Color), with attention to their intersecting identities. Chosen books are thoroughly selected, discussed, and vetted by two or more members.

Among the things we look for in curating this list is language. Unfortunately, ableist language has become a major reason for otherwise outstanding books not making the list. Most authors have done a good job of replacing racist, sexist, antisemitic, homophobic, and transphobic terms, both in addressing and describing characters and as metaphors for what is undesirable.

Not so with ableist terms. Words like “stupid,” “idiotic,” “dumb,” “blind,” “deaf,” “lame,” and “crazy” pepper too many middle grade and YA novels. “But that’s how kids talk!” you may say. However, we as educators, librarians, and writers are trying to move the needle on this. As a child who had trouble understanding social rules and interactions, I regularly heard the first two of those insults (along with the r-word) referring to me, my decisions, and my actions. Those words stigmatized me and normalized my classmates’ bullying of me. These insults of my intelligence also didn’t tell my why my decisions and actions were flawed.

Ableist language stigmatizes children with disabilities, both directly and by equating disability with negative outcomes. It also lacks precision, as these are general insults that don’t address why something is negative. If you say, “That movie was stupid,” we don’t know if the movie was boring, or the characters/story didn’t seem plausible, or the ending was predictable or contrived.

In addition to finding other more precise terms to describe people and events, authors can find ways to call out ableist language. For instance, in the middle grade novel A Place at the Table, co-authored by Saadia Faruqi and Laura Shovan, Pakistani-American protagonist Sara’s mother scolds her for calling classmates “stupid” (but like many kids her age, she keeps doing it). There’s a scene in my YA novel Torch in which Lída and Štepán share their experiences of hurt when people treat them as less than intelligent and equate them to barnyard animals. Leslie Connor’s middle grade novel The Truth as Told by Mason Buttle centers a middle schooler whose learning disabilities lead not only to vicious bullying but also to the community’s assumption that he’s guilty of a crime he didn’t commit. Often, young readers don’t understand that the terms they use cause distress to their classmates and can lead to negative consequences in the long term — like disabled children coming to believe they are incapable or bad, or whole communities making assumptions about those children’s abilities and potential.

In addition to finding other more precise terms to describe people and events, authors can find ways to call out ableist language. For instance, in the middle grade novel A Place at the Table, co-authored by Saadia Faruqi and Laura Shovan, Pakistani-American protagonist Sara’s mother scolds her for calling classmates “stupid” (but like many kids her age, she keeps doing it). There’s a scene in my YA novel Torch in which Lída and Štepán share their experiences of hurt when people treat them as less than intelligent and equate them to barnyard animals. Leslie Connor’s middle grade novel The Truth as Told by Mason Buttle centers a middle schooler whose learning disabilities lead not only to vicious bullying but also to the community’s assumption that he’s guilty of a crime he didn’t commit. Often, young readers don’t understand that the terms they use cause distress to their classmates and can lead to negative consequences in the long term — like disabled children coming to believe they are incapable or bad, or whole communities making assumptions about those children’s abilities and potential.

In addition to my work on the We Are Kid Lit Collective, I’ve joined with a diverse group of disabled authors on a panel proposal for the 2023 NCTE conference in Columbus, Ohio in November. We will talk about the importance of non-ableist language in the books teachers and librarians use with their students and in the students’ own writing. We will discuss how illness and disability have been used as metaphors and list better substitutes for those words, as both direct descriptions and figurative language. Although the panel has not yet been approved, it has already received the sponsorship of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, and we will continue to present at SCBWI events, to address ableist language at the source so we don’t have to leave otherwise valuable books off our curated lists.

In addition to my work on the We Are Kid Lit Collective, I’ve joined with a diverse group of disabled authors on a panel proposal for the 2023 NCTE conference in Columbus, Ohio in November. We will talk about the importance of non-ableist language in the books teachers and librarians use with their students and in the students’ own writing. We will discuss how illness and disability have been used as metaphors and list better substitutes for those words, as both direct descriptions and figurative language. Although the panel has not yet been approved, it has already received the sponsorship of the Society of Children’s Book Writers and Illustrators, and we will continue to present at SCBWI events, to address ableist language at the source so we don’t have to leave otherwise valuable books off our curated lists.

Congrats on finishing your book!

Thank you! I hope my agent won’t decide that it’s a mess and I have to start over.