The Right Translator

After translating six picture books for small and medium-sized publishers in the United States, I’m now working on a middle grade novel for a Brazilian publisher. I’m not allowed to reveal much information about this project until it comes out, but I’m finding that publishers outside the U.S. are much more open to global literature and different types of stories and writing styles. While approximately 3% of children’s books published in the U.S. are translations, the percentage in non-English-speaking countries around the world ranges from 15% to 50%. And from what I’ve seen, the availability of translated works doesn’t always drown out local voices. Often, it spurs creativity and innovation. The insularity of U.S. children’s literature can stifle, as it has in the film industry where, Black Panther aside, the most interesting and insightful work comes from other countries. Check out A Fantastic Woman, this year’s Academy Award winner from Chile, or the gritty Russian film Loveless, or the underappreciated (in the U.S.) Spoor, and you’ll see what I mean.

These low numbers for translated children’s books in the U.S. are still an improvement over past years. I’ve noticed more literary presses moving into books for younger readers, among them Archipelago Books’ Elsewhere Editions and Restless Books’ Yonder. Elsewhere Editions specializes in picture books, while Yonder Books focuses on middle grade and young adult. Publishers in the UK are also expanding their offerings to include books for children and teens.

One of the UK publishers has regularly sent me their children’s books for review, and in reading them, I’ve noticed a wide range of approaches to translating for young readers. One of the pitfalls of an adult literary publisher moving into translating for children is understanding the differences between “kidlit” and adult literature. Leaving aside YA/adult crossover titles and the elusive New Adult category, they really are two separate worlds, and it’s important for publishers who want to expand to choose translators who read literature for children and know its issues and conventions, who have experience writing and/or translating children’s books, and who are part of the children’s literature community.

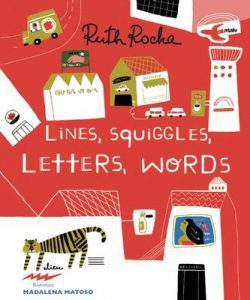

What are some of the differences? Again, this varies by age group, but one big difference is the amount of “domestication” — in other words, changing proper names and other content to make the story more familiar to young readers and to those who may read the book aloud to them. Picture books are made to be read aloud, and elementary school teachers often incorporate read-alouds of longer books into the school day. So, for example, an important character with the name João — a popular name in Portuguese — presents a challenge to the parent or teacher reading the book to a young child. In a YA novel, as in an adult novel, I would likely leave as is. In fact, in my YA historical novel set in Portugal, I had several difficult or tricky to pronounce names. (José is not pronounced in Portuguese the way it is in Spanish, and one major secondary character’s surname is Brandão.) But in a picture book or early middle grade, the name would likely be changed, as I changed João’s name in Lines, Squiggles, Letters, Words to the still non-English but more pronounceable Pedro. Italian translator Julia Heim describes other examples of domestication in her translation of the popular Geronimo Stilton chapter book series.

What are some of the differences? Again, this varies by age group, but one big difference is the amount of “domestication” — in other words, changing proper names and other content to make the story more familiar to young readers and to those who may read the book aloud to them. Picture books are made to be read aloud, and elementary school teachers often incorporate read-alouds of longer books into the school day. So, for example, an important character with the name João — a popular name in Portuguese — presents a challenge to the parent or teacher reading the book to a young child. In a YA novel, as in an adult novel, I would likely leave as is. In fact, in my YA historical novel set in Portugal, I had several difficult or tricky to pronounce names. (José is not pronounced in Portuguese the way it is in Spanish, and one major secondary character’s surname is Brandão.) But in a picture book or early middle grade, the name would likely be changed, as I changed João’s name in Lines, Squiggles, Letters, Words to the still non-English but more pronounceable Pedro. Italian translator Julia Heim describes other examples of domestication in her translation of the popular Geronimo Stilton chapter book series.

Another issue is child-friendly language. I received a review copy of a book in which the publisher had used a translator with impeccable credentials as a professor and linguist. However, the middle grade novel was riddled with academic language and ten-dollar words where a vivid and fun one-dollar word would have been a better choice. Dialogue didn’t capture the way preteens actually talk. In most children’s and YA books in the U.S., “said” is the dominant speaker tag and writers aren’t encouraged to seek variations such as “explained,” “described,” and “averred.” If one is writing an academic article or a work of criticism, these words come in handy, but children’s book writers typically do not use language that gets in the way of telling their story. Writers — and translators — should have a sense of drama, of placing the reader inside the story, and how language can contribute to that.

A final thing that an experienced translator (who may also be an author) for children and teens should address is the conventions of storytelling in the U.S. This doesn’t necessarily mean following those conventions to the point of altering the story, because one of the reasons to introduce translated literature is to show other ways of seeing the world and turning it into story. Changing elements of a story — or leaving them as they are even though some readers may find them incomprehensible or even offensive — is not a decision a translator should enter into lightly. Choosing a translator who is familiar with popular story structures and debates over cultural authenticity in children’s and YA literature means that such decisions will likely be made in a thoughtful and considered manner, contributing to both the integrity and accessibility of the work.

Thank you so much for this thoughtful post! So much to chew on. BTW, I just received my copy of Three Balls of Wool. It’s fantastic! I’m grateful that you helped make it accessible to US readers.

Thank you, Ruth! It was an honor for me to work on Three Balls of Wool — such an important story for our world today.

A fascinating post, Lyn. Thank you so much for walking us through these elements of translation!

I’m glad you found the piece useful, Sandra. I’m looking forward to going to Bologna with you next year! It’s already in my calendar (and I turned down a panel invite to AWP because the two conferences are the same weekend).