Translation and Writing Historical Fiction: #WorldKidLit Month

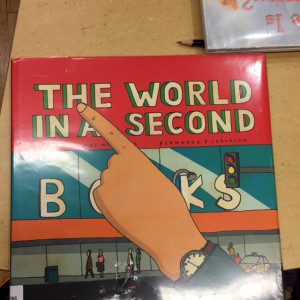

I became a translator after publishing four novels, two of them YA historicals set in Chile and among Chilean exiles living in the United States in the 1980s. My fluency in Spanish allowed me to read untranslated primary sources and to interview activists and former political prisoners when I traveled to Chile at the beginning of 1990. However, I’d never thought of becoming a translator until I lived in Portugal in 2012 and upon my return was approached to translate the picture book that would become The World in a Second.

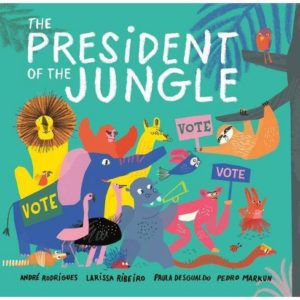

The World in a Second came out in 2015. Over the next five years, I would translate six more published books — five picture books released in the U.S. and a middle grade novel released in a trilingual (Portuguese, Spanish, English) edition in Brazil. My most recent translation was the timely 2020 picture book The President of the Jungle.

During the time I translated children’s books, I also worked on my own stories — picture books, middle grade proposals, and completed YA manuscripts — but none of them found a home. I loved my translation work — I still do — but I wanted to create original works as well. My sales drought lasted almost six years until in September 2019 I received offers on two separate books, my middle grade verse novel MOONWALKING, co-authored with Zetta Elliott, and my YA novel TORCH. My time in “author jail” had ended!

Now that I’m working on edits for these novels, I’m finding new ways that being a translator has enriched my writing and led me to think about questions of language and style in a new way. I’m also leaning on my friends and colleagues in the translation community to help me with my work.

A book I translated presents the basic principles of democracy, including the loser of a presidential election doesn’t get to stay on as president.

This is especially true in the case of TORCH, a novel set in Communist Czechoslovakia in 1969 and told from the points of view of three misfit teenagers whose mutual best friend dies in an act of protest against the Soviet invasion of their country. One of the principal issues I’ve encountered is the extent to which I should “Americanize” character and place names. The Czech language has many diacritical marks, some of which are not at all familiar to readers in the Americas. Those who know Spanish and Portuguese are familiar with the acute accent, the tilde (~), and perhaps the cedilla (ç) but what about the upside-down rooftop symbol known as the haček? And what about a six-letter name with diacritical marks on three of those letters, like Štěpán?

I’ve read many kids’ books by Latinx (or Latine, as it’s preferred in Latin America) authors that have Spanish words and phrases sprinkled throughout and in most cases leave the reader unfamiliar with the language to deduce the meaning from the context. That said, many readers in the U.S. know some Spanish or have friends who do. The same can’t be said for Czech, a language with few speakers in the U.S. and fewer than 20 million throughout the world, a language considered one of the more difficult languages to learn. (Polish, the language spoken by JJ’s father and grandmother in MOONWALKING, is considered even more difficult.) To give an example of its difficulty, Czech has a nominative case, one form of a noun when you’re speaking about a person or object, and a vocative case, a different form of the noun when you’re addressing someone directly. For instance, one character’s name is Tomáš, but when Štěpán says “hi” to him, he would say, “Ahoj, Tomáši.”

Therefore, one of the challenges I face is balancing a flavor of the language, its accurate use, and accessibility to my readers. If I have one character greet another in Czech, I have to use the vocative case even though it may seem confusing. As a result, I’ve kept the sprinkling in of non-English words to a minimum. I’ve also decided to use Anglicized forms of address — Mr., Mrs., and Miss rather than pan, paní, and slečna; Aunt and Uncle rather than teta and stryc. This avoids the vocative case issue as well. As compensation to give a sense of the language, I’ve maintained all diacritical marks in character and place names. I talked to my editor about this trade-off, and she agrees with my solution.

A more difficult issue involves the way the characters refer to their fathers. For their mothers, it’s easier. Máma, but without the accent. Two characters’ fathers appear in the novel. I would have to use “táta” when they speak about their fathers, either in thoughts or in talking about them to the others. When they speak to their fathers, they’d address them as táti. However, Tomáš and Lída have very different relationships with their fathers, and I’d like what they call their fathers in scene and in their own minds to be different. Already, I use “his father” to refer to Štěpán’s father, who never appears in a scene and from whom Štěpán is somewhat estranged even before his arrest for a political crime. Tomáš’s father is domineering, and the boy fears and dislikes him but also depends on him. I’d considered using “Father” (which would translate to Czech as “otec” with the rarely-used vocative “otče”), but it’s a bit formal even for his family. And Lída is close to her father, her only parent and her protector in the past, even though his messy life has become her problem.

I talked this issue over with my friend Alex Zucker, who recently translated a Czech novel that takes place in a similar time period. Before the pandemic, when I was co-chair of the PEN Translation Committee, I organized a translators’ work-in-progress reading where Alex joined four other translators in presenting a selection from their work discussing their questions and challenges with the audience. Alex talked about how he debated using “táta” or “papa” in referring to the father of the itinerant family at the center of the novel. He ended up with “papa” because it avoided the differences in cases, it was more universally used, and he could parallel the family’s peregrinations with those of his literary heroes, Ernest Hemingway, aka “Papa.” (My own father, by the way, was a Hemingway fan who insisted his grandchildren call him Papa.)

I’m thinking about “papa” for a reason that’s different, yet similar: the music of the 1960s plays an important role in TORCH, as it did in the lives of so many young people in Czechoslovakia then. One of my favorite bands of the time is The Mamas & the Papas, and at least one of my characters is “California Dreamin’.”

For Lída and her father, Ondrej, I’m thinking of going with the more informal “Pa” despite its old-fashioned tone. In a way, it feels right for a relationship in which Lída has in many ways become the parent and Ondrej the child. Of the three main characters, she’s also the only one who has lived her life in a rural area or on the outskirts of towns rather than in the center, so a more “countrified” name for him feels right.

This is the second of two posts for #WorldKidLit Month, a celebration of international children’s books in translation. You can read my first one here. That said, translated literature is valuable every month. Explore the possibilities!