Family Heritage Trip, Part 2

In the middle of our stay with family in Berlin, Maddy and I took the train to Prague, stopping in Dresden on the way back. I’ve been to both places, in fact have a blog post devoted to my visit to Dresden in 2012, but it was Maddy’s first time and an opportunity to add another to her “30 countries by 30” quest.

A memorial to two young men who sacrificed their lives to resist Communist tyranny. This month is the 50th anniversary of the Soviet invasion that ended the Prague Spring.

We arrived in the middle of a heat wave that has baked most of Europe and contributed to devastating wildfires in Greece last month (including Kineta, a resort area west of Athens that Richard and I passed through on a tour to the Peloponnese region). While Maddy hit the shops in Prague, I climbed Vitkov Hill with VCFA schoolmate and multi-published author Ellen Yeomans to see the historical monument dedicated to the history of Czechoslovakia between 1918 and 1989.

While the size of Dresden’s Military History Museum shows the outsized role of the military in Germany’s history and its long tenure as a major European power, Czechoslovakia from 1918 to 1938 was a country carved out of the ruins of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, an experiment in democracy and self-rule of a people long accustomed to occupation and domination by others. Inter-war Czechoslovakia was a multicultural, multilingual nation incorporating Czech speakers from Bohemia and Moravia, Slovak speakers from Slovakia, and Germans and Hungarians living in the border regions.

As historian Tara Zahra describes in her 2011 book Kidnapped Souls: National Indifference and the Battle for Children in the Bohemian Lands, 1900-1948, Germans and Czechs coexisted relatively peacefully for centuries despite legitimate worry among Czech speakers that their language would be lost in the process. In fact, summer exchanges between Czech and German families in the Sudeten region was as much a way for German children to learn Czech as for Czech children to learn the far more spoken German tongue. As the countries around it succumbed to authoritarian regimes, Czechoslovakia remained a beacon of democracy and peace throughout the 1930s, until Hitler set his sights on the tiny country and the leaders of the Western powers succumbed in the infamous 1938 Munich Conference to which Czechoslovakia’s representatives were not even invited. A year later, with the Czech defenses in the mountains dismantled, Nazi forces took over the entire country, placing Bohemia and Moravia into a protectorate (ultimately presided over by the brutal Reinhard Heydrich) and installing a puppet regime in Slovakia.

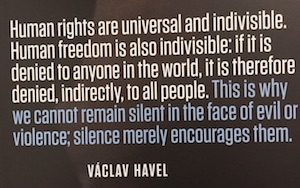

The sacrifice of a highly advanced multilingual democracy represents one of the most infamous moments of an infamous century, and it initiated another half-century of occupation and subjugation with the Soviet-backed Communists replacing the Nazis as wearers of the jackboot. Both the National Memorial on Vitkov Hill and the relocated and nicely revamped Museum of Communism at Republic Square in Prague explore life under the Communist dictatorship and the undercurrent of resistance that led to the 1968 Prague Spring, the Charter 77 movement, and in 1989 the Velvet Revolution that restored democracy to the country under the leadership of poet, playwright, and human rights activist Vaclav Havel. This coming Tuesday, August 21, is the 50th anniversary of the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia, which ended the reforms of the Prague Spring, the promise of “socialism with a human face.” Many who supported the Communist takeover in 1948 out of gratitude for the Red Army’s defeat of the Nazis and the promise of land reform turned against the Party in the wake of the invasion, the crushing of reforms, and the persecution of the reformers. One can see that changed attitude in the text of the Vitkov Hill exhibit, which is worth seeing for its monumental architecture and its artifacts despite the strenuous climb. (I should note that on the hot day Ellen and I visited, the museum was empty.)

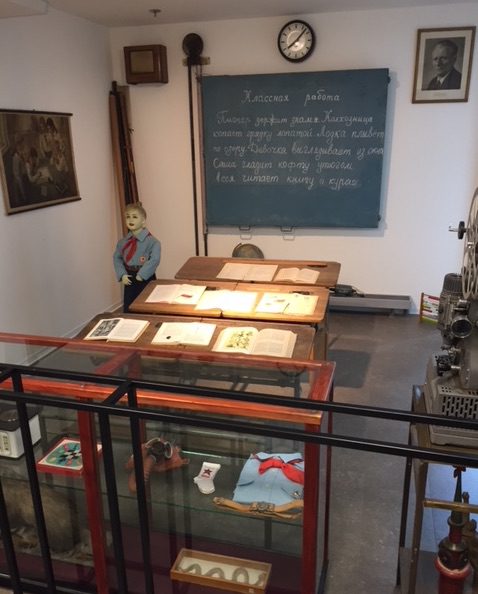

The next day, Maddy and I started early and saw the National Memorial to the Heroes of the Heydrich Terror at St. Cyril’s Orthodox Church, the place where Josef Gabčik, Jan Kubiš, and other Czech Resistance fighters hid after attacking the Nazi administrator’s convoy and fatally wounding him. The museum is small and was crowded that morning with people from around the world wanting to learn about this suicidal mission against one of the cruelest of Hitler’s minions. Later, both Maddy and I appreciated the Museum of Communism for its exploration of daily life under a regime of extreme repression. For most people, life goes on even without freedom, and people learn to keep their heads down and not to draw attention to themselves by complaining or being different in any way. Maddy, who is looking for her first year-long teaching position after graduating with her Masters in Elementary Education in December, lingered at the exhibit of a classroom in the early 1960s, complete with a lesson in Russian on the chalkboard and next to it a black-and-white portrait of Antonin Novotny, who ruled from 1953 to 1968.

As we walked around Prague, Maddy noted the reserve of locals in comparison with their German counterparts. Perhaps people accustomed to occupation tend to keep a distance from those who might occupy or overrun them, while those who are accustomed to occupying others approach the world with more assurance. Or perhaps it’s a matter of overtourism, which is related to the above theory and the subject of a future post because I’d be remiss as a travel blogger to ignore the problem. When Richard and I visited Prague in 2011, it was February and bitter cold (we landed in an ice storm) and we were pretty much the only international tourists in the city. When we visited an art museum, the staffer was eager to talk with us and excited that we liked the work of František Kupka, an early 20th century painter and graphic artist.

Maddy still needs to meet her “30 countries by 30” goal, so I don’t expect her to make a repeat visit to Prague, but the city is going into my “like a lot” if not “fell in love” category and I have a friend there. I don’t think I’d go in the summer next time because of the crowds and particularly the high number of “stag dos” or rowdy bachelor parties attracted by the cheap beer and decriminalized pot. (Interestingly, the decriminalization of all drugs in Portugal has not resulted in similar wild-party tourism, a topic I plan to address in my upcoming post on overtourism.) I’m planning to attend the Bologna Children’s Book Fair in March 2019 with a group of other VCFA’ers, and this will give me the opportunity for a return visit as well as a stopover in Bratislava (where I’m considering a major blogging project) and a trip to some of the smaller cities and towns of Slovakia and the Czech Republic as I track down more of my own family heritage.

Maddy still needs to meet her “30 countries by 30” goal, so I don’t expect her to make a repeat visit to Prague, but the city is going into my “like a lot” if not “fell in love” category and I have a friend there. I don’t think I’d go in the summer next time because of the crowds and particularly the high number of “stag dos” or rowdy bachelor parties attracted by the cheap beer and decriminalized pot. (Interestingly, the decriminalization of all drugs in Portugal has not resulted in similar wild-party tourism, a topic I plan to address in my upcoming post on overtourism.) I’m planning to attend the Bologna Children’s Book Fair in March 2019 with a group of other VCFA’ers, and this will give me the opportunity for a return visit as well as a stopover in Bratislava (where I’m considering a major blogging project) and a trip to some of the smaller cities and towns of Slovakia and the Czech Republic as I track down more of my own family heritage.